We hear the benefits of microservices architectures loud and clear; we hear the constant drum beat of how/why/by all means/etc you should be doing microservices; we know companies such as Amazon, Netflix and Gilt have successful microservices architectures.

However, as I’ve touched on in my blog post titled You’re not going to do microservices, getting microservices right – and being able to add your company or organization to the list of success stories – is difficult. Just deciding to use Dropwizard/SpringBoot/WildflySwarm/flat classloader/Docker etc doesn’t mean you’re doing microservices. In fact, prematurely breaking your apps/services down into smaller services has significant tradeoffs and could lead to a SOA on steroids disaster. Even the venerable Martin Fowler agrees with me.

So when we talk about the success stories of microservices at conferences, on developer blogs, etc. I think we’re missing the point. The successes aren’t about which dependency manager, or classloader structure, or linux container, or cloud service to use. They aren’t about mythical internet web-scale unicorns or their architects. I think it’s about something a bit more fundamental, albeit, less sexy than Docker/Kubernetes/SpringBoot.

The real success?

The real success stories of a microservice architecture are about how organizations that embrace small, cross-functional teams that engage with a flat, self/peer-management structure, are able to scale and innovate at levels unheard of in traditional organizational structures and do it wildly successfully.

Two-pizza team

I had the pleasure to work closely with teams at Amazon and learn about their organizational culture. One tenant of their structure was that organized teams had to follow the “two-pizza” rule. Simply, a team could not be larger than what two pizzas could feed. The thinking behind this was summed up by an Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos quote:

Managers: We need more communication on and between our teams

Bezos: No. Communication is terrible”

To create and sustain autonomous, creative, innovative teams, you don’t want “more communication” you want “effective communication.” This is easier said than done, but it starts by having smaller groups of people work together. They get to know each other better, they form relationships, trust, and motivation. There is less chance of group think or social loafing.

J Richard Hackman studied team and group dynamics found that the communication links between members grows as you add more people to a team following this equation:

(n * n-1) / 2

As the number of links grow within a team (ie, more members), the communication degrades and team productivity similarly degrades. The number Hackman settled on was something less than 10. Amazon teams usually consist of 6-8 members. Navy Seals work in combat teams of 4. The number is not hard and fast, but it should be small. In fact, just stop and think about social situations you encounter ever day. Is it easier to have a conversation and relate to one another in large groups (ie, at a wedding, people break off into smaller groups to chat)?

I highly recommend reading Hackman’s article here about why teams don’t work.

Cross functional

I saw this quote recently that can perfectly sum up why a team should be cross-functional:

Bad behavior arises when you abstract people away from the consequences of their actions

Creating more functional silos seems to have the effect of “encouraging bad behavior”. For example, developers should be focused on writing and delivering quality code. They should also be thinking about non-functional aspects like security, performance, scalability, high availability, etc. However if you start creating application Database teams, or QA teams, or separate operations teams, then developers seem to focus on “getting features in” and throwing the rest over the proverbial fence.

Do these sound familiar?

- “I dont have time for testing, QA does that”

- “I don’t have to know how the database works, the DBA does that”

- “I just code it, Operations makes it highly available”

The opposite to this, is to have teams be cross-functional: have a database, operations, test, person on the same team. Or have individuals take on multiple roles. This is what a lot of these internet unicorn companies do (Amazon, Netflix, Facebook, Google, etc). This way, what your team builds, you’re responsible for it. There’s no chance for “throwing over the fence” and absolving yourself of responsibility of building quality software. In this vein, there is no such thing as a DevOps team. These practices are ingrained in all of the teams.

Conways law

Conway’s Law helps tie the above two points together. Conway stated:

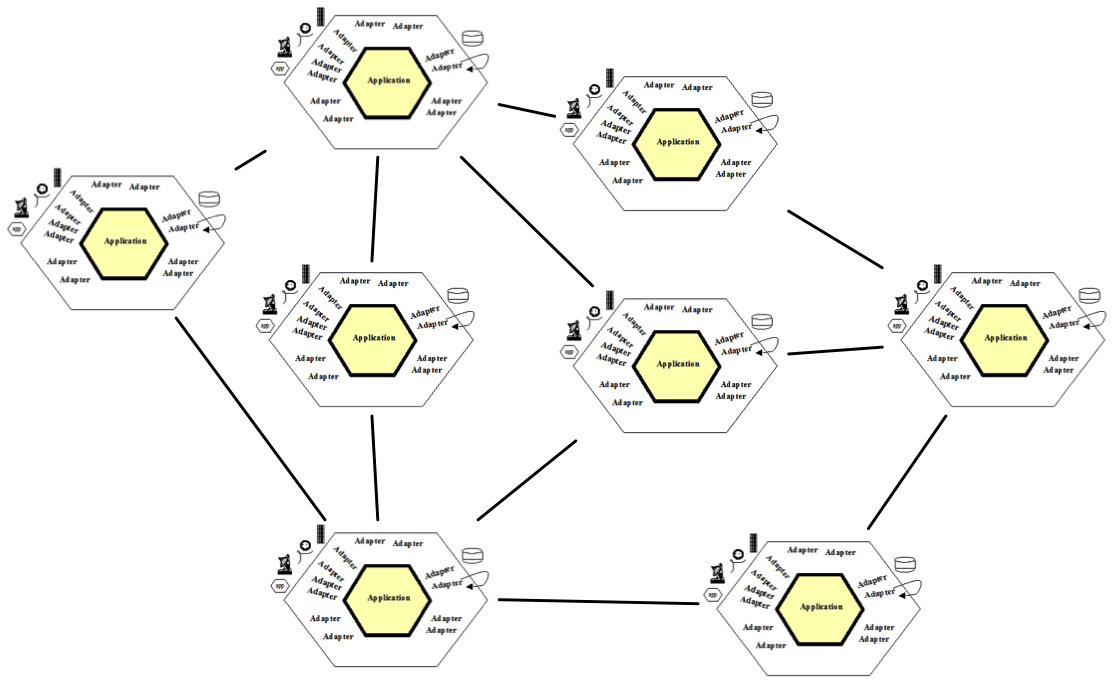

organizations which design systems … are constrained to produce designs which are copies of the communication structures of these organizations

And we see some of the rigidity of traditional architectures (including those that embraced SOA) because of this simple law. Hierarchical, siloed, organizations build systems that are rough copies of themselves. People, processes, and communication have been molded around this structure for ages. This does not scale in such a way to allow autonomy and innovation. So if we want to build scalable systems like we talk about with microservices, we have to start with building scalable organizational structures. Then Conways law follows that the communication structures (within and between smallish, loosely coupled, cross-functional teams) we create will be found in the systems we design.

Open-source communities?

If you squint, you’ll start to see that these small, cross-functional, microservices teams start to look like and behave like small open-source projects do. People work together, they aren’t afriad to share their opinions, they’re passionate about building quality software and since they’re small and focused they seem to follow conway’s law by building modular software. They are developers, testers, ops, etc all working together toward a common goal. And that’s what DevOps and Microservices is really about.

SOA vs Microservices?

Again, to reiterate, in my opinion the success stories about microservices that we hear about are not necessarily technological success stories, and we run the risk of missing the point and going down the same path SOA took. SOA had a lot of the same principles that are the foundation of microservices, but SOA lost sight of the finish line. People startin doing SOA just because it was SOA, and vendors, committees, and consortiums came together to give us specs we “needed”. Ultimately, SOA had some of the same goals about organizational structure, but those got lost in WS-* spcs.

There is no doubt tooling and processes are important, even in a microservices world, but those should follow the principles that are rooted in organizational structures.

Tooling

This post is already getting long, but in my next post, I’ll want to point out some of the things we’re doing in the OpenShift and fabric8io projects that aim to simplify things for cross-functional developers working in microservices teams but without overlooking the important foundations of social, organziational, and communication aspects of a microservice team.