I’ve talked quite a bit recently about the evolution of microservices patterns and how service proxies like Envoy from Lyft can help push the responsibility of resilience, service discovery, routing, metrics collection, etc down a layer below the application. Otherwise we risk hoping and praying that the various applications will correctly implement these critical functionalities or depend on language-specific libraries to make this happen. Interestingly, this service mesh idea is related to other concepts that our customers in the enterprise space know about, and I’ve gotten a lot of questions about this relationship. Specifically, how does a service mesh relate to things like ESBs, Message Brokers, and API Management? There definitely is overlap in these concepts, so lets dig in. Feel free to follow along @christianposta on Twitter for more on this topic!

Four assumptions

1) Services communicate over a network

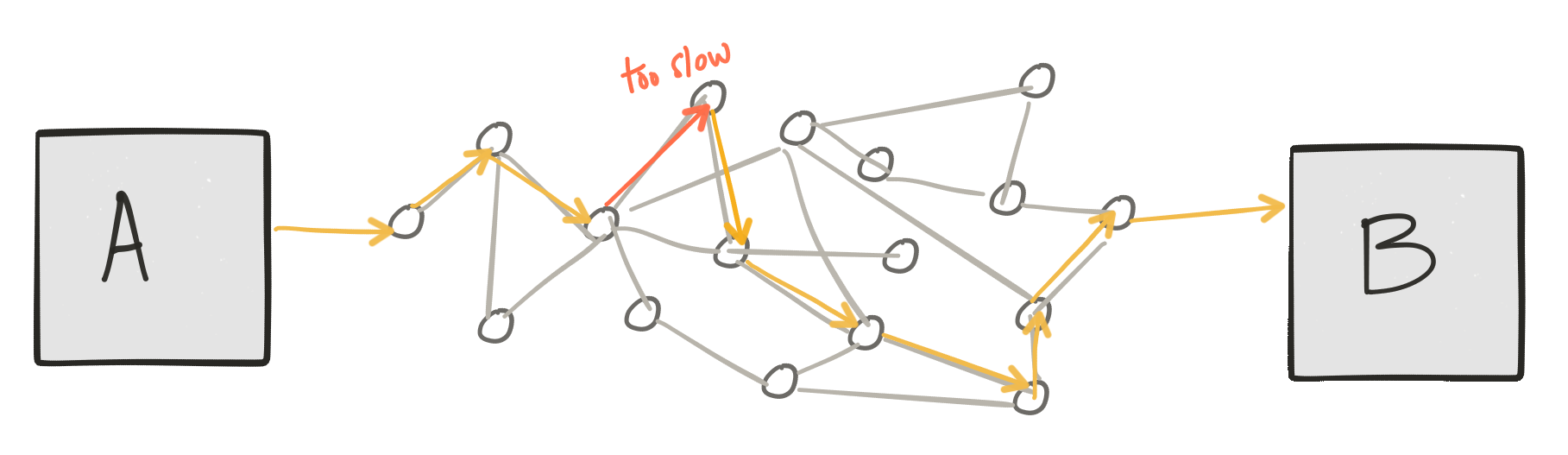

First point to make: We’re talking about services communicating and interacting with each other over asynchronous, packet-switched networks. This means they are running in their own processes and in their own “time boundaries” (thus the notion of asynchronicity here) and communicate by sending packets across a network. Unfortunately, there are no guarantees about asynchronous network interaction: we can end up with failed interactions, stalled/latent interactions, etc, and these scenarios are indistinguishable from each other.

2) If we look closely, these interactions are non-trivial

Second point to make: how these services interact with each other is non-trivial; we have to deal with things like failure/partial success, retries, duplicate detection, serialization/deserialization, transformation of semantics/formats, polyglot protocols, routing to the correct service to handle our messages, dealing with floods of messages, service orchestration, security implications, etc, etc. Many things can, and do, go wrong.

3) There is a lot of value in understanding the network

Third: there is a lot of value in understanding how applications communicate with each other, how message get exchanged, and potentially a way to control this traffic; this point is very similar to how we look at Layer 3/4 networking; it’s valuable to understand what TCP segments and IP packets are transversing our networks, controlling the rules around how to route them, what’s allowed, etc.

4) It’s ultimately the application’s responsibility

Lastly: As we know through the end to end argument, it’s the applications themselves that are responsible for the safety and correct semantic implementation of their purported business logic – no matter what reliability we get from underlying infrastructure (retries, transactions, duplicate detection etc) our applications must still guard against user’s doing silly things (submitting an order twice) – anything that helps support this is implementation/optimization details. Unfortunately, there is no way around this.

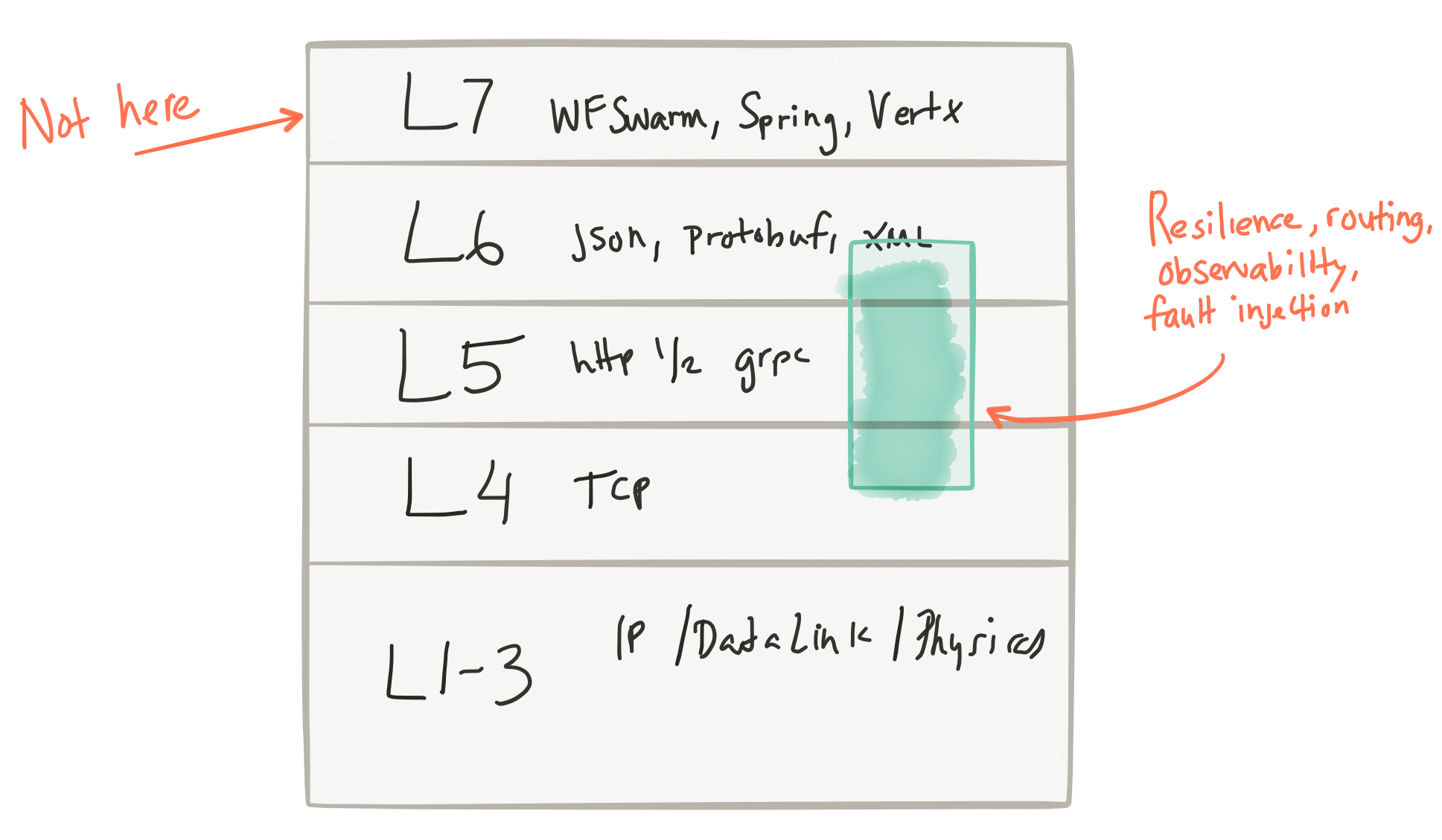

Application Network Functions

I think no matter what services architecture you prefer (microservices, SOA, object request brokers, client/server, etc, etc) these points are all valid – however, in the past we’ve blurred the lines about what optimizations belong where. In my mind, there are horizontal application networking functions that are fair game to optimize out of our applications (and put into infrastructure – just like we do at lower levels of the stack), and there are others that are more closely related to our business logic that should not be so readily “optimized” out.

Network

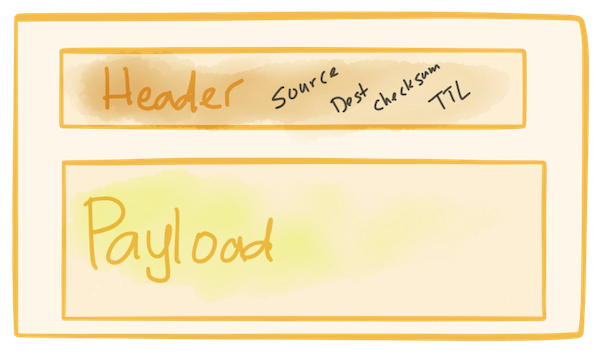

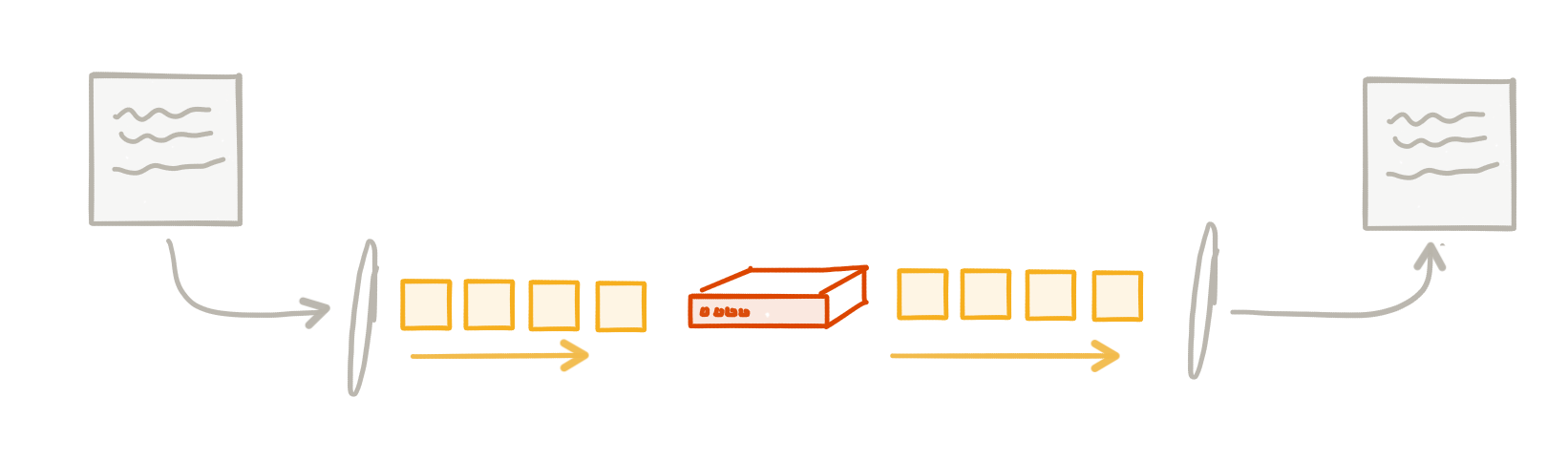

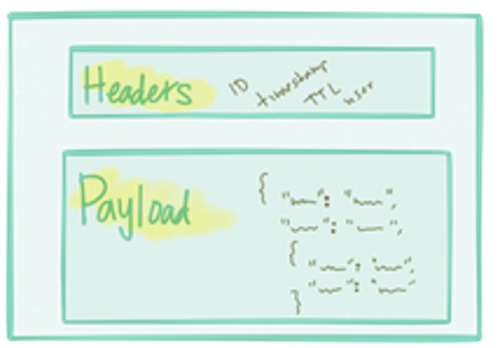

Let’s take a quick step back and understand what the networking looks like (at a super trivial and high level :)) below our applications. When we send a “message” from one service to another, we pass it to the networking stack of our operating system which then figures out how to put it onto the network. The network, depending on what level, deals with transmission units (frames, datagrams, packets) etc. These transmission units usually consist of a structure that includes a “header” and a “payload” with the “header” containing enough metadata about the unit that we can do basic things like routing, ack tracking / de-deuplication, etc.

These transmission units are sent through different points in the network which decide things like whether or not to allow the unit through, whether to route it to a different network, or to deliver it to its intended recipient. At any point along the path, these transmission units can be dropped, duplicated, reordered, or delayed. We have higher-level “reliability” functions like TCP that exist in the networking stack in our OS that can track things like duplicates, acknowledgements, timeouts, ordering, lost units etc and can retry on failures, re-order packets and so on.

These types of functions are provided by the infrastructure and are not mixed with business logic – and this scales quite well (internet scale!) I just ran into a wonderful blog from Phil Calcado that explains this nicely as well.

Application

At the application level, we do something similar. We split up conversations with our collaborator services into transmission units of “messages” (requests, events, etc). When we make calls over the network, we have to be able to do things like timeout, retry, acknowledge, apply backpressure and so on for our application messages. These are universal application-level problems and will always crop up when we build services-style architectures. We need to solve them somehow. We need a way to implement application network functions.

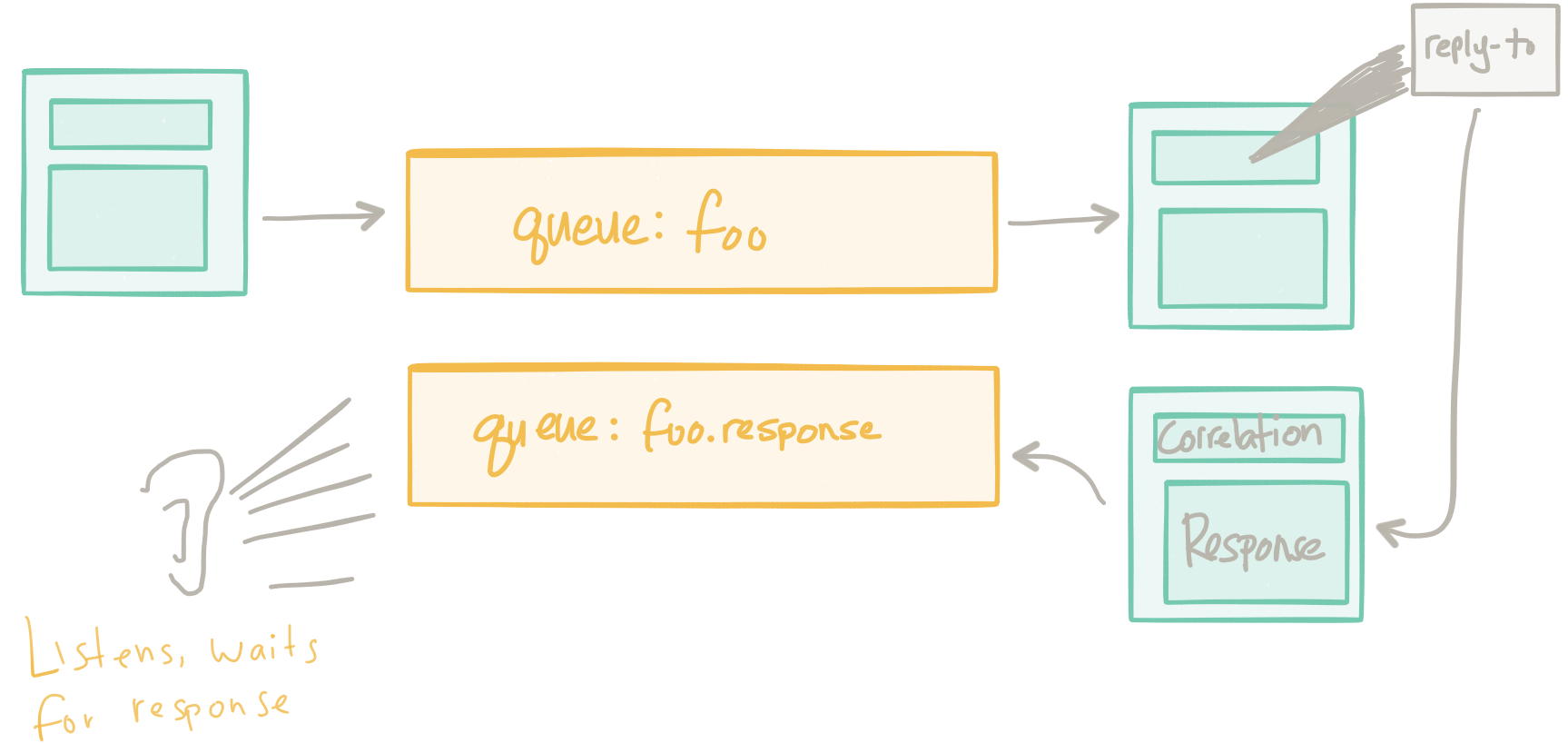

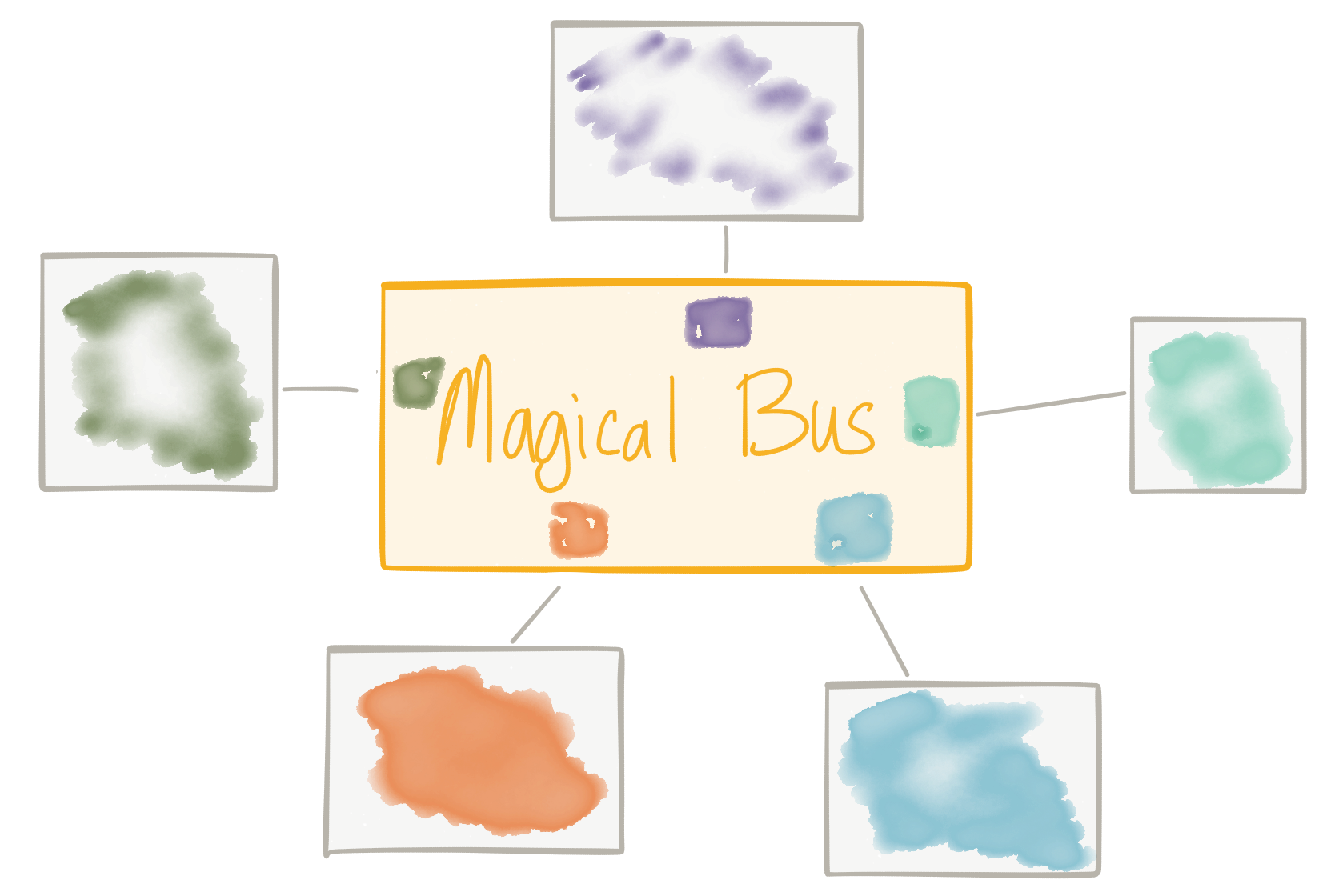

For example: In the past we tried solving these problems with messaging brokers. We had a centralized set of messaging oriented middleware (maybe even with multi-protocol support so we could transform message payloads and “integrate” clients) that was responsible for delivery of messages between clients. In a lot of examples I’ve seen, the pattern was to basically do Request/Reply (RPC) over the messaging system.

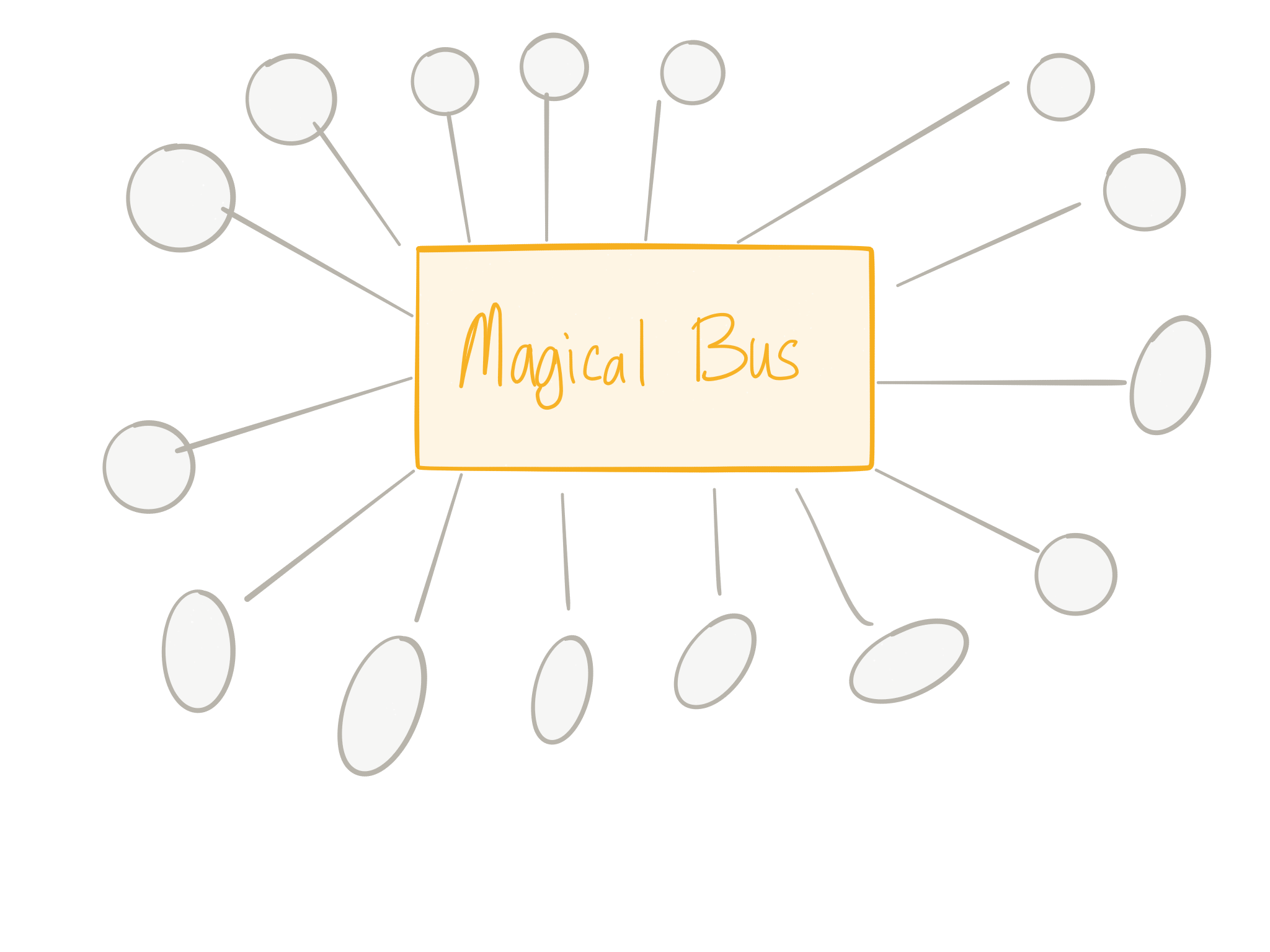

This tacitly helped solve some of these problems around application network functionality: things like load balancing, service discovery, back pressure, retries, etc were all delegated to the messaging brokers. Since all traffic was intended to flow through these brokers we had a central spot from which to observe and control network traffic. However, as @tef_ebooks points out on twitter this approach is quite heavy handed/overkill. It also tends to be a big bottleneck in an architecture and wasn’t really as easy as we thought when it came to traffic control, routing, policy enforcement, etc.

So we tried to do that too. We thought “well, let’s just add routing, transformation, policy control” to the centralized message bus we already had. This was a natural evolution actually – we could use the messaging backbone to provide centralization/control and application network functions like service discovery, load balancing, retries, etc – but, we’d also layer on top more things like protocol mediation, message transformation, message routing, orchestration, etc. We felt if we could push these seemingly horizontal things down into the infrastructure, our applications could be lighter/leaner/more agile etc. These concerns were definitely real the ESB evolved to helped fill those.

As a colleague of mine Wolfram Richter pointed out “Regarding ESB-the-concept, IBM’s white paper from 2005 regarding SOA architectures (http://signallake.com/innovation/soaNov05.pdf chapter 2.3.1) defines ESBs as follows:”

The enterprise service bus (ESB) is a silent partner

in the SOA logical architecture. Its presence in the

architecture is transparent to the services of your

SOA application. However, the presence of an ESB is

fundamental to simplifying the task of invoking

services – making the use of services wherever they

are needed, independent of the details of locating

those services and transporting service requests

across the network to invoke those services wherever

they reside within your enterprise.

Seems legit! Even seems like some of the things we’re trying to do with the newer technology that is cropping up. And you know what? We are!!! The problems from yesteryear have not just magically disappeared, but the context and landscape has changed. We’re hopefully able to learn from our past unfulfilled promises.

For example, in the days of SOA as envisioned by the big vendors (writing endless specs upon specs via committee etc, rebranding EAI etc.), what we found was three things that contributed to the undelivered promises of the “ESB”:

- organization structure (let’s build another silo!)

- technology was complicated (SOAP/WS-*, JBI, Canonical XML, proprietary formats, etc)

- business logic was needed to implement things like routing, transformation, mediation, orchestration, etc

The last bullet point is what overdid things. We wanted to be agile but we distributed vital business logic away from our services and into an integration layer owned by another team. Now when we wanted to make changes (agile) to our services, we couldn’t; we had to stop and synchronize significantly with the ESB team (brittle). As this team, and this architecture, became the center of the universe for many applications we can understand how the ESB team became inundated with requests (agile) but were unable to keep up (brittle). So although the intentions were good, we found that mixing core application networking functions with functions that are much more related to business logic is not a good idea. We end up with bloat and bottlenecks.

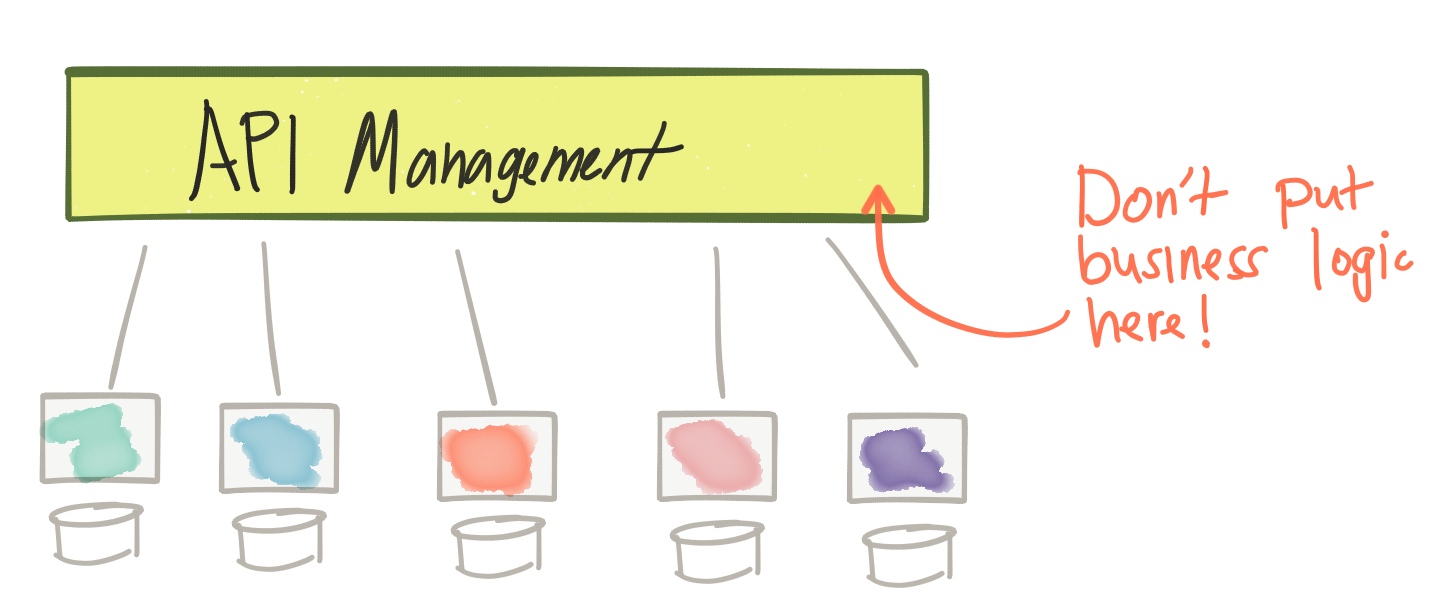

Then along came the REST revolution and the API-first mindset. This movement was partly a backlash against the complexity of SOAP/ESB/SOA coupled with a new way to think about turning our data inside out (via APIs) to spark new business models and scale existing ones. We also introduced a new piece of infrastructure to our architecture: the API management gateway. This gateway provided us a centralized way of controlling outside access to our business APIs through security ACLs, access quotas and plans for API usage, metrics collection, billing, documentation etc. However, just like we saw in the previous examples with the message brokers, when we have some kind of centralized governance we run the risk of wanting to accomplish too many things with it. For example, as API calls are coming through our gateway why don’t we just add things like routing, transformation, and orchestration? The problem with this is we start going down the path of building an ESB which combines infrastructure level networking concerns with business logic. And this is a dead end.

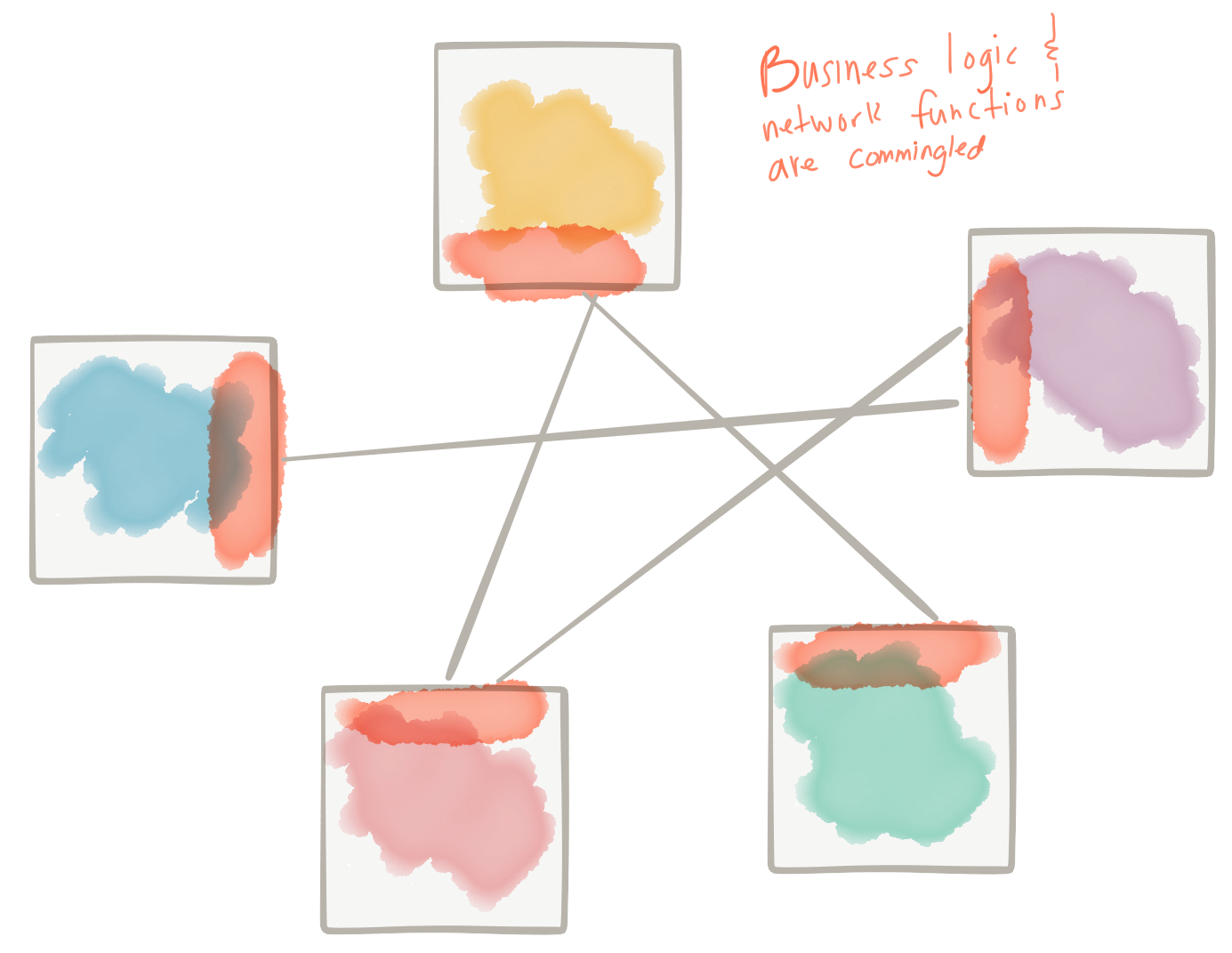

But we still had to solve for the points listed above between our services even for the REST / non-SOAP era (not just the so-called “North-South” traffic, but we needed to solve for the “East-West” traffic interactions). Even more challenging, we needed to figure out a way to use commodity infrastructure environments (aka, cloud) which tended to exacerbate these problems. Traditional message brokers, ESBs, etc would not fit this model very well. Instead, we ended up writing the application networking functions inside our business logic. … we started seeing things like the Netflix OSS stack, Twitter Finagle, and even our own Fuse Fabric crop up to solve some of these problems. These were typically libraries or frameworks that aimed to solve some of the points made above but they were language specific and were intermingled in our business logic (or our business logic spread throughout our infrastructure). There were problems with this model as well. This approach required a massive amount of investment in each language/framework/runtime. We basically had to duplicate efforts across languages/frameworks and expect all of the different implementations to work efficiently, correctly, and consistently.

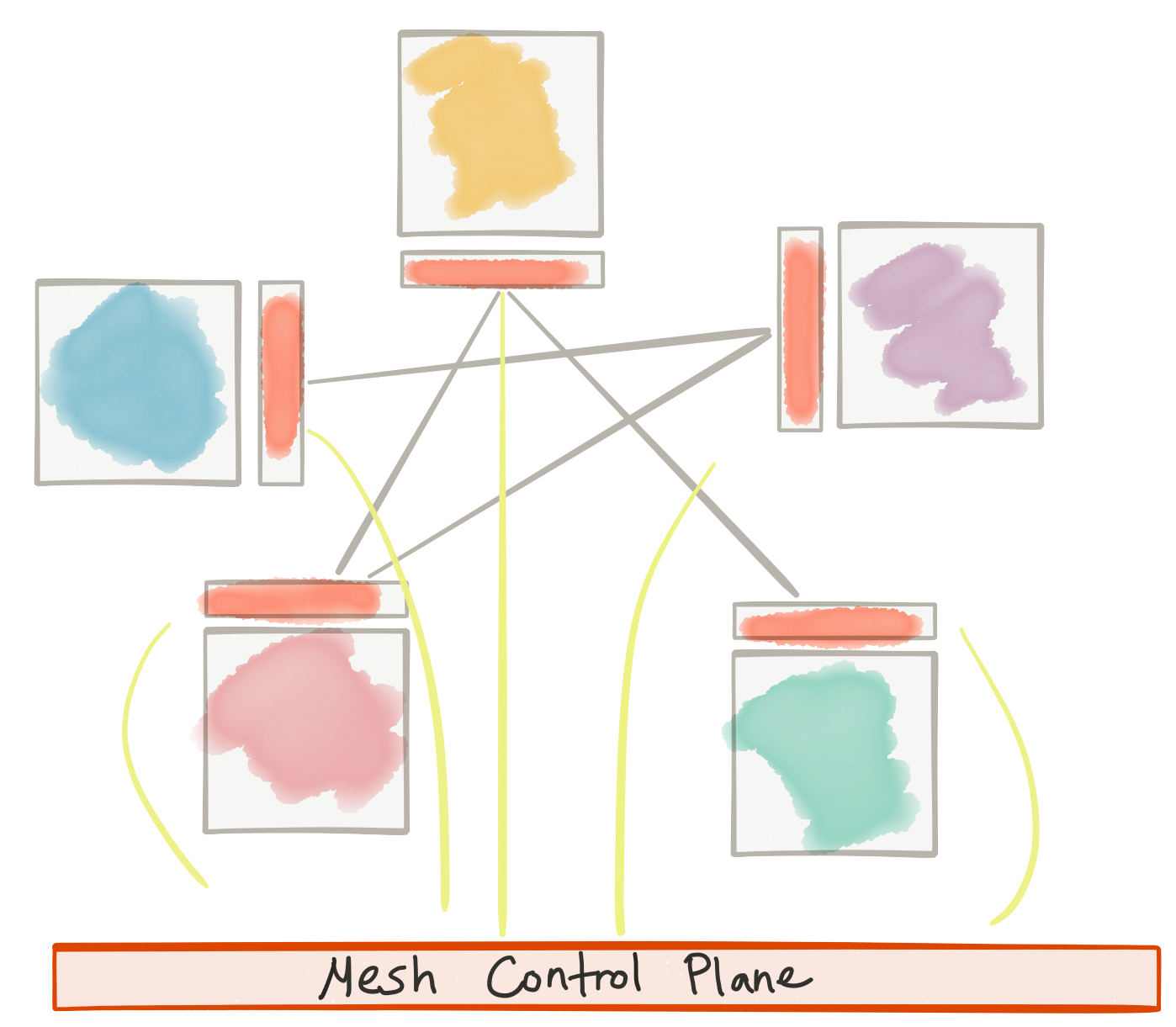

What has emerged through these trials and tribulations is something that allows us to push application network functions down into the infrastructure with minimal overhead and high decentralization with the ability to control/configure/monitor application-level requests – tackling some of the earlier issues. We’ve been calling this the “service mesh”. A nice example of this is the istio.io project based on Envoy Proxy. This lets us architecturally separate the concerns of application networking functions from those that are focused on differentiating business logic:

As Phil Calcado explains, this is very similar to what we do with the TCP/IP networking layer; networking functions are pushed out into the Operating System and are not directly part of the application.

So how is this related to…

With the service mesh, we’re explicitly separating application network functions from application code, from business logic, and we’re pushing it down a layer (into the infrastructure – similar to how we’ve done with the networking stack, TCP, etc.).

The network functions in question include:

- simple, metadata-based routing

- adaptive/client-side load balancing

- service discovery

- circuit breaking

- timeouts / retries / budgets

- rate limiting

- metrics/logging/tracing

- fault injection

- A/B testing / traffic shaping / request shadowing

Things that are specifically NOT included (and are more appropriate in your business logic/applications/services, not some centralized infrastructure):

- message transformation

- message routing (content based routing)

- service orchestration

So how’s a service mesh different than…

ESBs

- Overlap in some of the network functions

- Decentralized control points

- Application-specific policies

- Does not try to deal with business-logic concerns (mapping, transformation, content-based routing, etc)

Message Brokers

- Overlap (from a 30,000 ft level) in service discovery, load balancing, retries, backpressure

- Decentralized control points

- Application-specific policies

- Does not take responsibility for messages

API Management

- Overlap in certain aspects of policy control, rate limiting, ACLs, Quotas Security

- Does not deal with the business aspects of APIs (pricing, documentation, user-to-plan mapping, etc)

- Similar in that it DOES NOT IMPLEMENT BUSINESS LOGIC

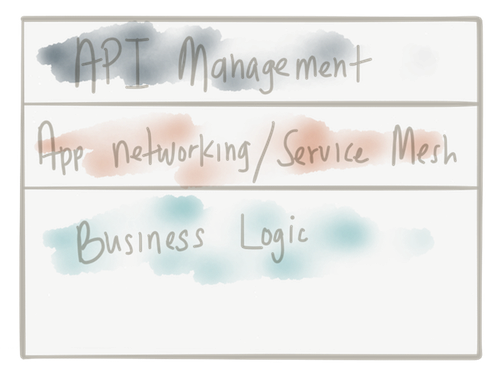

With respect to API Management, there does seem to be some overlap but I like to think of these things as highly complementary. API Management provides higher-order semantics about APIs (like documentation, user sign up/access, lifecycle management, API plans for developers, metering for billing and chargeback, etc). Lower-level application networking like circuit breakers, timeouts, retries, etc are crucial when calling APIs but these fit nicely in the service-mesh layer. The points of overlap like ACLs, rate limiting, quotas, and policy enforcement etc can be defined by the API Management layer but actually enforced by the service mesh layer. In this way, we can have full end-to-end policy and access control as well as enforce resilience for North/South traffic and East/West traffic. As @ZackButcher (from the Istio team) on twitter pointed out “As you get larger, east-west traffic starts to look more like north-south from the perspective of producing and managing your service.”

Bringing it all together

We need to take an API-first approach to our systems architectures. We must also solve for things like resiliency. We also find we have integration challenges. And in many ways, an architecture built on asynchronous event passing and event processing as a backplane for your APIs and microservice interactions can help to increase availability, resilience, and reduce brittleness. In the past, solving for these problems has been challenging as competing products and solutions overlapped and conflated concerns – as we move to cloud architectures it’s becoming apparent we need to tease apart these concerns and put them into the proper spots in our architecture otherwise we’ll succumb to some of the same lessons learned.

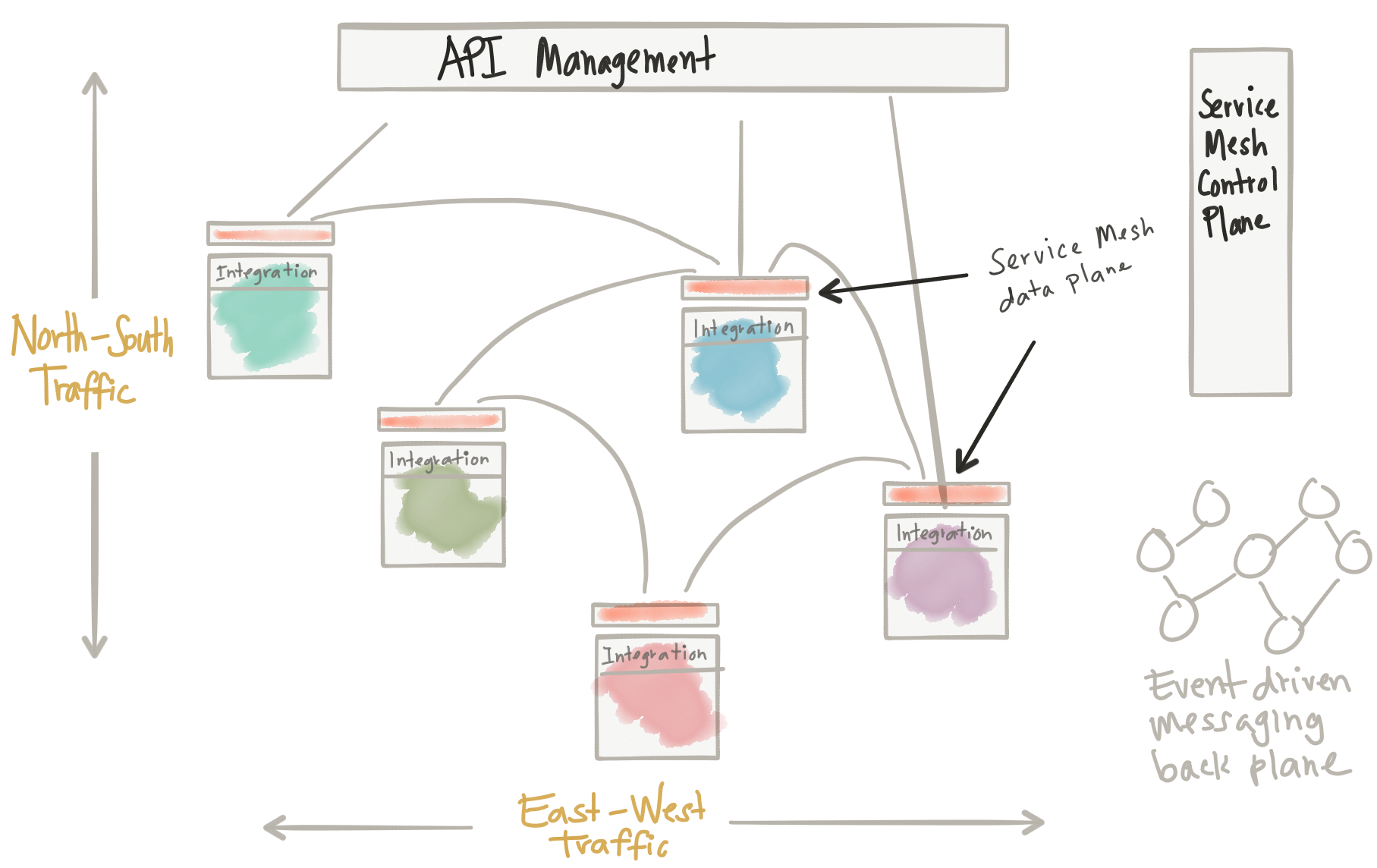

From the diagram above, we see a few things:

- API management for ingress north/south traffic

- Service Mesh (control + data plane) for application network functions between services

- Service Mesh enforcing API Management policies for east/west traffic

- Integration (orchestration, transformation, anti-corruption layers) as part of the applications

- Event-driven message back plane for truly asynchronous / event-driven interactions

If we hearken back to the four assumptions I made up front, here’s how we push to solve them:

- Point One: services interact over the network – we use a service mesh data plane / service proxies

- Point Two: interactions are non-trivial – implement business integration in the services themselves

- Point Three: control and observability – use API Management + Service Mesh Control plane

- Point Four: your specific business logic; use service mesh / messaging / etc for optimizations

Can you really separate out the business logic!?

I think yes. There will be blurry lines, however. In a service mesh, we’re saying that our application should be aware of application network functions but they should not be implemented in the application code. There is something to be said about making the application smarter about what exactly the application network function / service mesh layer is doing. I think we’ll see libraries/frameworks building in some of this context. For example, if Istio service mesh raises a circuit breaker, retries some requests, or fails for a specific reason, it would be nice for the application to get more understanding or context about these scenarios. We would need a way to capture this and communicate it back to the service. Another example would be to propagate tracing context (distributed tracing like OpenTracing) between services and have this done transparently. What we may see is these thin application/language specific libraries that can make the application/services smarter and allow them to take error-specific recourse.

Where do we go from here

Each parts of this architecture are at varying levels of maturity today. Even so, taking a principled approach to our services architecture is key. Separate business logic from application networking. Use the service mesh to implement application networking, the API management layer to handle higher-order API-centric concerns, business specific integration lives in the services layer, and we can build data intensive / available systems through the event-driven backplane. I think as we go forward, we’ll continue to see these principles unfold in specific technology implementations. At Red Hat (where I work) we see technologies like 3Scale, Istio.io on Kubernetes, Apache Camel, and messaging technology like ActiveMQ Artemis / Apache Qpid Dispatch Router (including non Red Hat technologies like Apache Kafka IMHO) as strong building blocks to build your services architecture that adhere to these principles.