As I work with enterprise users adopting AI agents, questions around authorization, impersonation, and delegation come up again and again. OAuth is already a delegation protocol, so where does it fall short for agentic systems? How do familiar flows like Authorization Code or Microsoft’s long-standing “On Behalf Of” model apply when the caller is no longer just a user or an app but an AI agent making decisions on its own? Who is actually acting? Who is accountable? This post unpacks where traditional OAuth fits, where it breaks down, and what changes when agents enter the picture.

OAuth Delegation

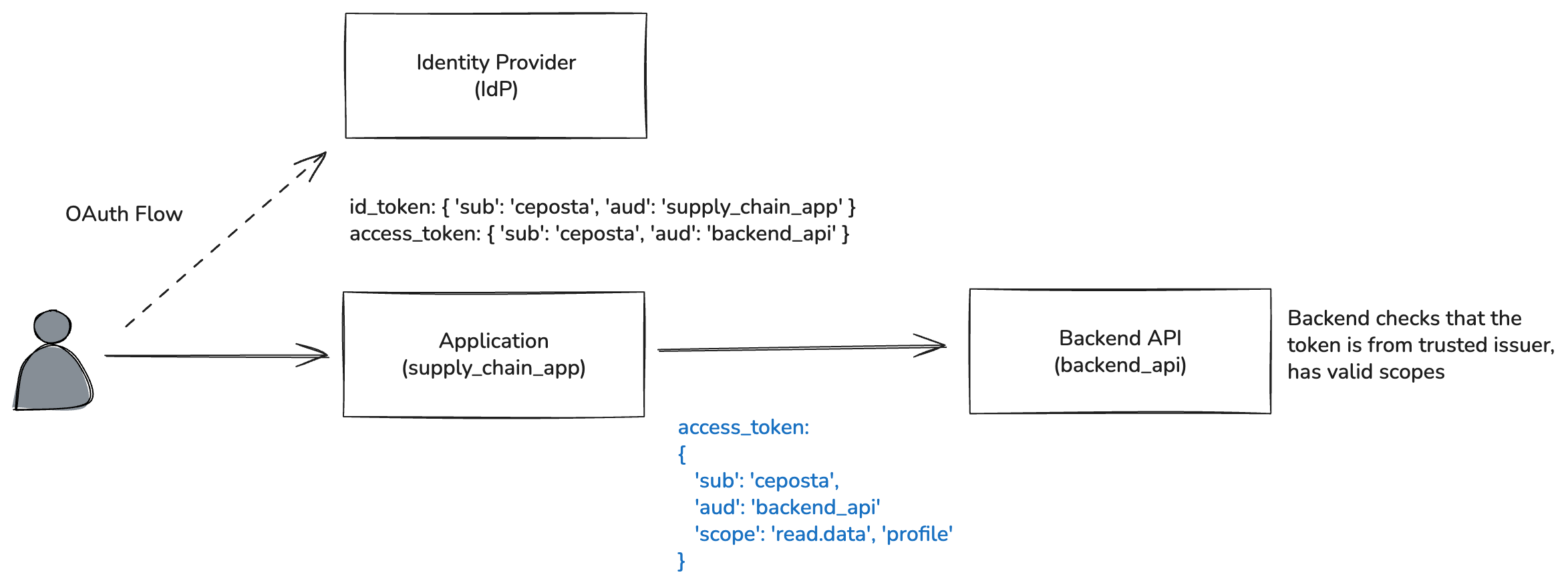

OAuth is fundamentally an authorization delegation protocol. What is being delegated? A user delegates limited access of their data to an specific application.

In OAuth terms, the user is the resource owner, the application is the client, and the backend API is the resource server.

For example, let’s say a User (ceposta) has some data exposed on a Backend API (backend_api). Maybe it’s a system that knows about my laptop ordering history. Someone else (third-party?) built an application (supply_chain_app) that helps me optimize my laptop ordering and I really want to use it but it needs access to my ordering history (backend_api).

When I login to the Application, it can walk me through the OAuth Authorization code dance to consent “delegating read-only access” to the Backend API for my data.

Now, if I consent, the Application will get a limited-scope access_token it can use to call the Backend API to read data about my ordering history. From the perspective of the Backend API, this delegated call is indistinguishable from the user calling the API directly. The sub represents the user, and the application’s involvement is largely invisible at authorization time. This ambiguity is usually acceptable when the client is a traditional application acting at a user’s request. But it becomes problematic as systems grow more distributed and especially when autonomous agents begin making decisions and calling APIs on their own.

So what about the Microsoft On Behalf Of flow how does it fit?

On Behalf Of

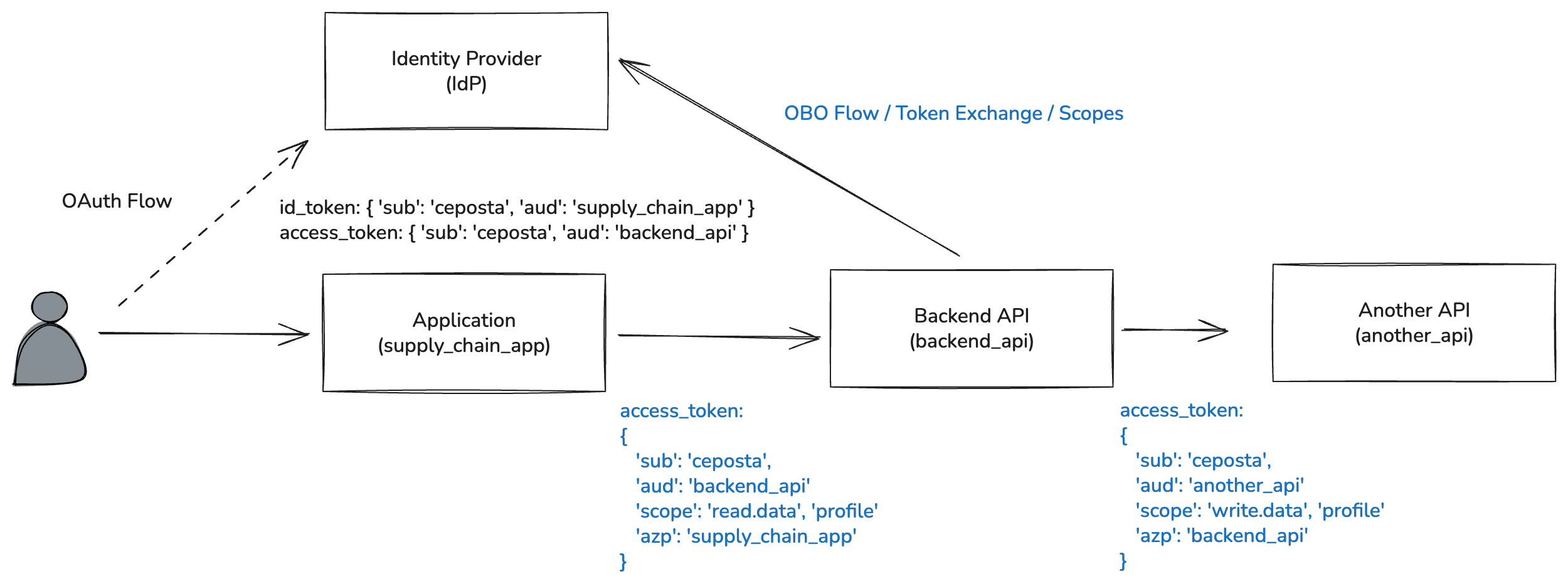

OAuth delegation works well when an application directly calls a backend API. But modern systems rarely stop there (hello microservices?). If the backend API calls another API as itself (with a service account and its own permissinos) then the authorization changes (where’s the user?). If it just forwards the user’s access token directly then the audience and scope are wrong (too broad, irrelevant, etc). Something must re-issue a token with the user’s identity preserved, the correct audience, likely re-scoped/narrowed scope.

That’s where Microsoft’s “On Behalf Of” flow enters the picture. This flow is about controlling how identity propagation happens across service boundaries. OBO is a way to preserve the user’s identity while reissuing a token that is valid for a different resource and constrained to what both the user and the calling service are allowed to do.

What happens in this case is the Backend API has a token scoped for its use (sub: ceposta, aud: backend_api, scp: read.data) but it needs to call Another API (another_api), but it needs to maintain the user’s identity and potentially re-scope the token according to what the User and the Service is allowed.

So the Backend API requests an on-behalf-of flow with the identity provider (Microsoft Entra in this example):

POST /oauth2/v2.0/token

client_id=backend_api

&grant_type=urn:ietf:params:oauth:grant-type:jwt_bearer

&assertion={BackendAPIToken}

&requested_token_use=on_behalf_of

&scope=api://another_api/write.data

Although Microsoft has an explicit OAuth flow called On Behalf Of, the generic form of this, and what you may see in other Identity Providers is RFC 8693 Token Exchange.

Up to this point OBO assuems the calling service is a known intermediary which needs to execute requests as the user. That assumption breaks down when the caller is an autonomous agent that decides when to act, what to call, and how far to propagate a user’s authority without a human directly in the loop. “On Behalf Of” has now become a question of responsibility.

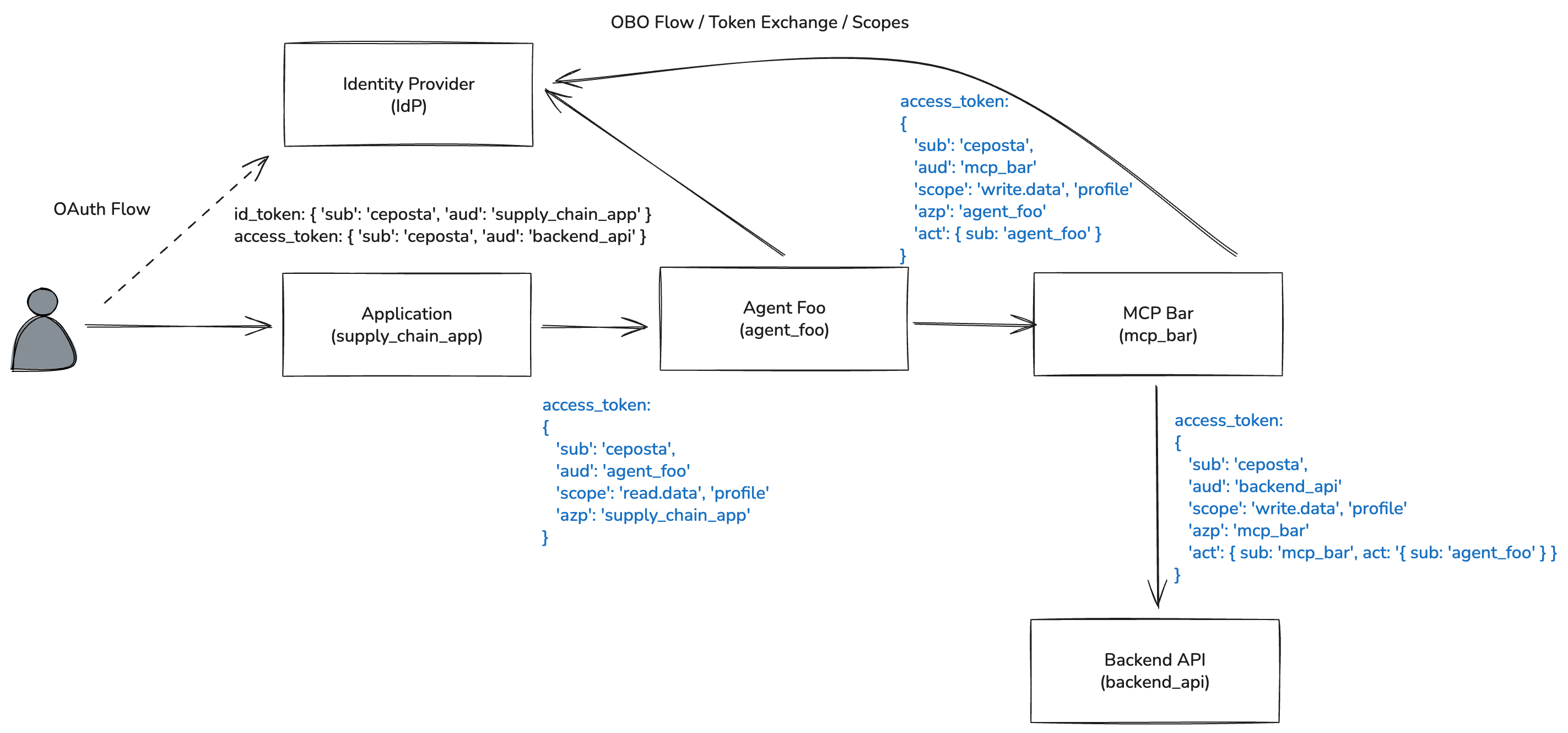

Agentic On Behalf Of

In classic OBO flows, a service propagates a user’s identity while executing a request it did not originate. With AI agents, the agent is making decisions based on current context and is no longer “forwarding intent” for the user, but rather, creating intent. This is a crucial difference between the previous two delegation mechanisms with the user (or determinsitic servics) directly involved.

The problem with this is, when AI agents are the callers, we want to know this. An API will want to know if an Agent is calling its API especially when doing things on behalf of a user. I have covered this in some detail in the past, but for brevity, to support agentic OBO safely in an enterprise environment systems need to account for :

- decision attribution and accountability - who made the decision to take this action? in AI agent usecases, the Agent makes the decision and we need to attribute this

- compliance and audit - clear records of which AI agents touched which/sensitive systems and what actions were performed; need to distinguish between humans and agents; traceability of agent actions

- capability gap - an identity (AI Agent) to authorize for capabilities not available to the user / ability to revoke, etc

To support these requirements, we need to be able to do OBO/Token Exchange that not only preserves the User’s identity, but also makes clear the Agent identity, who authorized the call, and what caused the calls.

Microsoft Entra Agent ID OBO

One concrete example of agentic OBO in practice is Microsoft Entra’s Agent Identity support. Entra extends traditional OBO flows to explicitly model an AI agent as a first-class actor, rather than treating it as an invisible intermediary.

In an Entra Agent OBO flow, the resulting access token still represents the user as the subject of the authorization decision. The sub claim remains the user, preserving user-based access controls and consent semantics. What changes is that the agent is now explicitly identified as the actor initiating the call.

This is reflected in the token through the agent’s application identity (appid) along with a set of agent-specific “actor facet” claims. These claims allow upstream services and policy engines to determine that the request was initiated by an AI agent, the agent is acting on behalf of a specific user, the call occurred within an OBO context.

For example using the token below:

{

"aud": "https://graph.microsoft.com",

"iss": "https://sts.windows.net/<tenant-id>/",

"app_displayname": "My Test Agent",

"appid": "<agent-identity-id>",

"appidacr": "2",

"idtyp": "user",

"name": "Christian Posta",

"scp": "openid profile User.Read email",

"sub": "93m3ed3gY2h-GzDAQ0wyVuqRu1hLfBsDDXdealS9RLQ",

"xms_act_fct": "11 9 3",

"xms_ftd": "Plb9b3Bh1d3xh5HcmYti2q5fLAcc2OeWln56eacITYcBdXNzb3V0aC1kc21z",

"xms_idrel": "1 8",

"xms_par_app_azp": "<blueprint-client-id>",

"xms_st": {

"sub": "XX5D9M_IIoFoqCuAVHsJgQhJRzq05-Tp2GcpgLl8p7Y"

},

"xms_sub_fct": "2 3",

"xms_tcdt": 1657299251,

"xms_tnt_fct": "3 8"

}

This example Agent ID OBO token shows the subject is the User (me), but the appid is the Agent’s identity and the xms_idrel, xms_sub_ct, and xms_act_fct together signal this is an AI Agent OBO. See the reference docs for more on how that works.

Entra’s approach is one way to surface agent identity in OBO flows; more general solutions rely on standards-based token exchange mechanisms that make actor relationships explicit across platforms.

Agentgateway Token Exchange

In Solo.io agentgateway, we use the standard RFC 8683 approach for token exchange and we can tie the agent identity to whatever identity mechanism used by the platform. For example, SPIFFE is a popular workload and Agent identity mechanism. It can also use Entra Agent ID, etc.

So just like in the previous example, the sub claim would be the User’s IdP sub identity along with any additional claims (roles, groups, entitlements, etc). Following the RFC 8693, we use the act claim to identity that an Agent is calling on behalf of the user. And we can nest these claims so we can see things like causality and authorization. That is, “agent A called agent B which is why agent B is calling API foo”.

Here’s a common OBO token for this:

{

"act": {

"act": {

"act": {

"sub": "spiffe://cluster.local/ns/default/sa/supply-chain-backend"

},

"sub": "spiffe://cluster.local/ns/default/sa/supply-chain-agent"

},

"sub": "spiffe://cluster.local/ns/default/sa/market-analysis-agent"

},

"act_depth": 3,

"aud": [

"company-mcp.default",

"agent-sts"

],

"iss": "agent-sts",

"name": "mcp-user",

"realm_access": {

"roles": [

"supply-chain",

"ai-agents"

]

},

"sub": "e58704d6-daea-4c75-848d-b1cfb6819015",

"typ": "OBO"

}

To see this in action, take a look at the following videos:

- Part One: https://youtu.be/MJAAuco8K_I

- Part Two: https://youtu.be/uvmzsQMmAp8

- Part Three: https://youtu.be/gPXeV_lWMJU

Scope Narrowing for OBO Flows

A common question with On Behalf Of and token exchange flows, especially in agentic scenarios, is whether an agent can request scopes or step up privilege that did not exist on the original call / user token.

At first glance, this can feel like privilege escalation. An agent appears to be “asking/doing more” than the user initially granted or assumed. In practice, however, OBO flows do not grant authority based on what is requested, they grant authority based on policy.

In an OBO or RFC 8693 token exchange, the resulting access token represents the intersection of three things:

- what the user is allowed to do

- what the calling service or agent is allowed to do

- what the target API is willing to accept

Requesting a scope is simply an input into this decision. The identity provider (or security token service) evaluates the request and issues a token only if all policy conditions are met. If the user is not authorized for the scope, or the agent is not permitted to act with that scope, the exchange fails.

This is why token exchange must be understood as authority reduction, not amplification. Each hop through an OBO flow produces a token that is more constrained and targeted to a specific audience, narrowed in scope, and bound to a particular actor.

In agentic scenarios, this distinction is especially important. An agent may have capabilities that a user does not, and a user may have permissions that an agent should never exercise. OBO flows allow these boundaries to be enforced explicitly, rather than implicitly inherited.

The result is a token that preserves user context while making clear:

- which agent initiated the action

- what authority was intentionally delegated

- and what was explicitly denied

Wrapping Up

OAuth style flows already solve delegation. What OAuth never considered was autonomy and non-deterministic applications making decisions.

As AI agents move from assistants to actors, long-standing authorization assumptions start to fail. Identity systems that assume every delegated call is user-driven lose the ability to answer basic questions about responsibility, intent, and accountability.

Agentic On Behalf Of addresses this by separating “who the data belongs to” from “who decided to act”. By making actors explicit, constraining authority through token exchange, and preserving user context without collapsing identities, agentic OBO turns a growing blind spot into a controllable design surface.

If you’re working on an AI Agent / MCP project and have questions about agent identity and access management, please reach out and connect /in/ceposta!