You’re probably saying “Wait. You already wrote a blog telling me the hardest part of microservices was my data. So what is the hardest part? That? or Calling your services?”

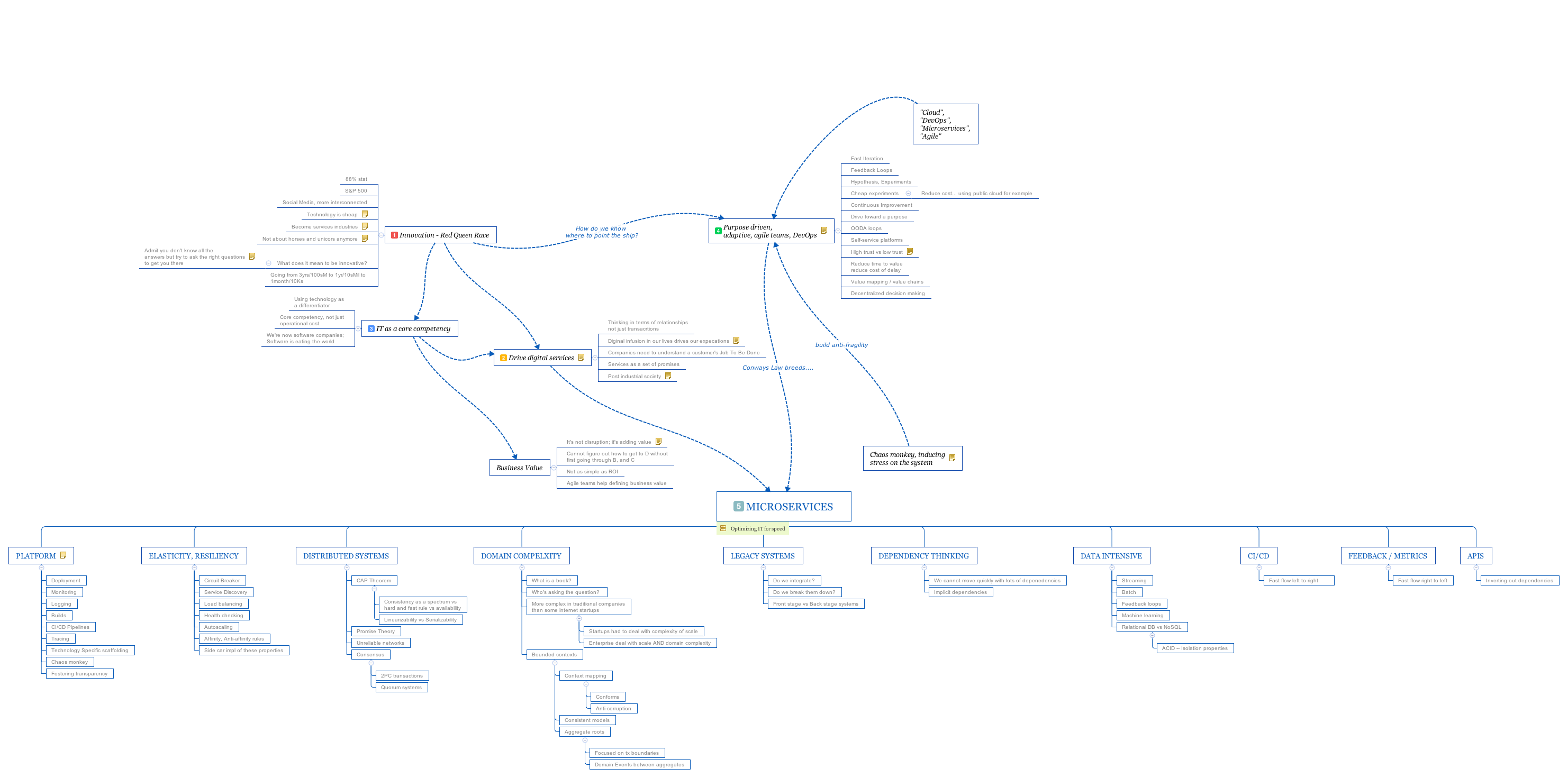

There are lots of hard parts of microservices, actually. The blogosphere/conferencesphere/vendorspehere tends to romanticize microservices but from the technology perspective, we’re building distributed systems. And distributed systems are hard.

I work very closely with Red Hat’s top strategic customers to help them successfully navigate these hard parts, implement services architectures to stay competitive, innovate, and succeed in generating business value. I also stay very close to how quickly technology is evolving in the open-source communities. Follow me @christianposta as I often speak/write/discuss these topics. But my background is integration and asynchronous messaging, so the topic at hand is something near and dear to my heart: getting services to talk to each other using various conversations patterns.

As we continue to iterate on these concepts surrounding services architectures, we inevitably have to deal with a major source of these hard problems. I’m hoping that as you explore and begin implementing microservices, you’ve seen and digested the fallacies of distributed computing. But I also recommend Jeff Hodges’ “Notes on Distributed Systems for Young Bloods”.

I feel like we’ve been chasing our tail a bit with past solutions to some of these problems. We’ve been trying to find the holy grail of “how do we just let developers write the business logic that will deliver value and try to abstract away distributed systems.” We’ve done things like making service calls look like local calls by abstracting away the network with local interfaces (mmmm… CORBA, DCOM, EJBs, etc). But then we learned that’s a bad idea. Then we switched to things like WSDL/SOAP/code generation to get away from the brittleness of those other protocols, but we continued the same practice (SOAP client code generation?). Some folks actually did make these approaches work, and they’ve got many scars to show. Let’s look at some of the problems encountered when simply calling your services:

- Failures or latency

- Retries

- Routing

- Service discovery

- Observability

Failures? Or Latency…

What happens when we send a message to a service? For the purposes of this discussion, that request gets broken down into smaller chunks and routed over a network.

We deal with the fallacies of distributed computing because of this “network”. Our applications communicate over asynchronous networks which means there is no single, unified understanding of time. Services live in their own understanding of what “time means” and that could be (is) different from other services. More to the point, these asynchronous networks route packets based on availability of paths, congestion, failures in hardware, etc. There is no guarantee a message will get to its intended recipient in bounded time (note, this same phenomenon does not occur in “synchronous” networks which have a unified understanding of time).

So that sucks. Now it becomes impossible to determine failure or just slowness. But if a customer makes a request to search for concerts on our ticket-selling website, we don’t want to wait until the universe melts away. We want to be responsive, and at some point just fail the request. So we add timeouts to our services. But, one does not simply add timeouts to their services.

When you’re making downstream requests, we can’t afford to be slow because our donw-stream network interactions are slow. Some timeouts to think about setting:

- How long it takes to establish a connection to a downstream service so we can send a request

- Whether or not we’re getting responses back to our requests

Quick side note: the huge advantage to building a system as a services architecture is speed which includes speed of making changes to the system. We value autonomy and frequent deployments of our system. But when we do this, we can quickly find ourselves in odd situations where timeouts don’t properly work well together.

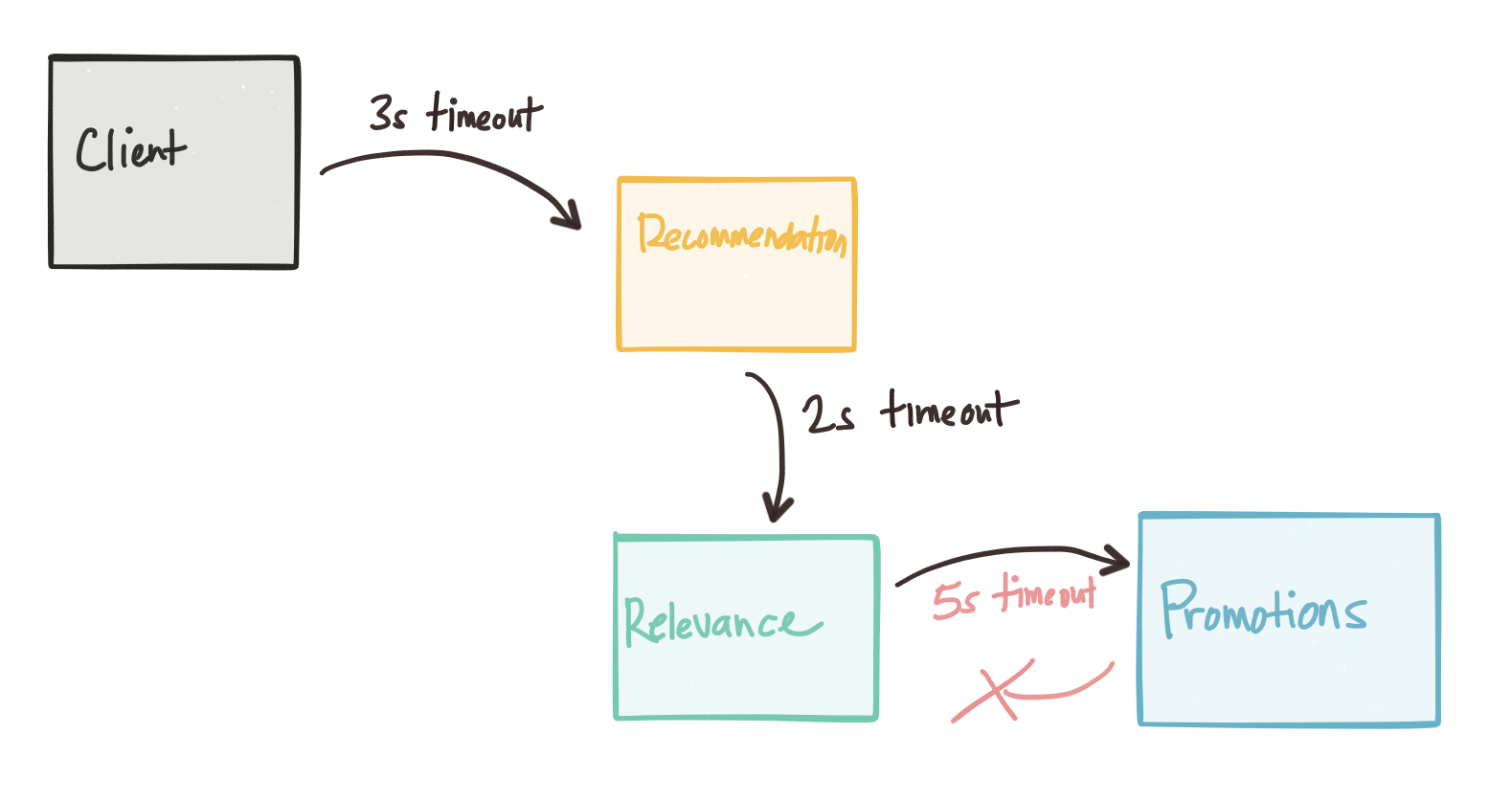

Consider our client application sets a timeout of 3s to get a response back from a recommendation engine. But the recommendation engine also consults a relevance engine. So it makes a call with timeouts set to 2s. This should be okay because our upstream service call will wait for at most 3s. But what if the relevance engine has to converse with a promotions service? What if that timeouts end up being set to 5s? Our testing (unit, local, integration) of the relevance engine seems to pass all tests even under latent operations because our timeouts are set to 5s and the promotion service either doesn’t take that long, or the relevance engine properly ends the call after the timeout elapses.

What we end up with is a nasty, very difficult to debug situation when lots of calls are coming in (or not… this can happen at any time because our network is “asynchronous” remember?). Timeouts are great, until they’re not.

Retries

Since we really don’t have any bounded-time guarantees in distributed systems, we will need to timeout at some point when things are taking too long. Now we end up in a situation of “what do we do after we timeout?”. Do we just throw a nasty HTTP 5XX to our caller? Do we take some advice about 3 easy things to make microservices resilient and promise theory and fallbacks? Or do we retry?

If we retry, what if we’re making a call that changes data on the downstream service? Check that 3-easy-things blog aforementioned, but I also cover some of that from the data/consistency perspective in my blog (and associated talks) the hardest part of microservices was my data.

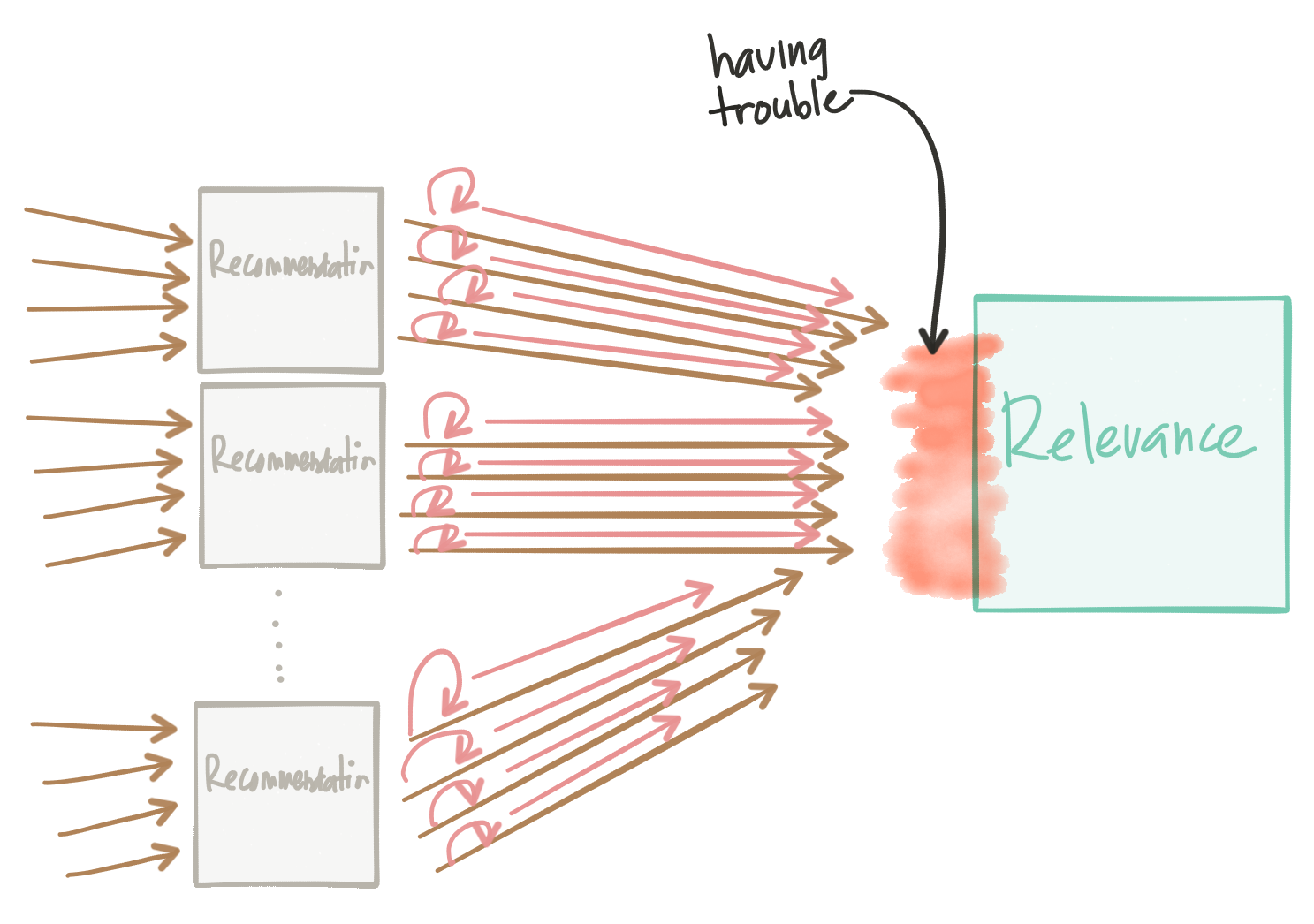

But more interestingly, what if our downstream service starts failing and we end up retrying every request? What if we have 10s or 100s of instances of our recommendation engine calling our relevance engine, but our relevance engine is timing out? We end up with a variant of the Thundering Herd Problem. This ends up DDoS our services even as we try to remedy and slowly bring back the affected service.

We need to be careful with our retry strategy. Exponential retry backoff can help, but may still experience the same issues.

Routing

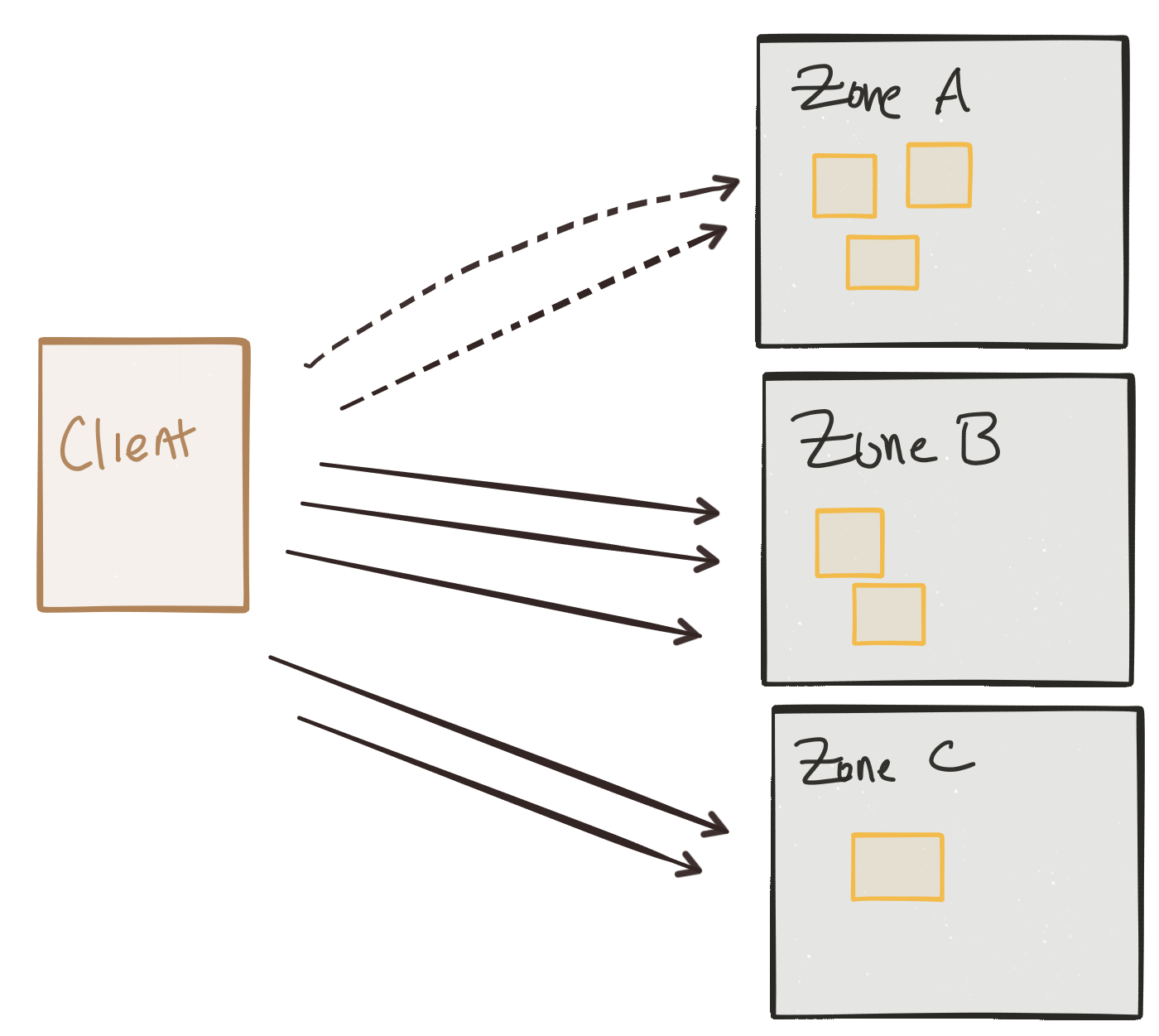

Because we deploy our services with resilience in mind, we ideally have multiple instances running in different fault-tolerance zones such that some zones can fail without taking down the availability of our services. But as things start failing, we need a way to route around these failures. But we may have other reasons for service traffic routing in/between fault-tolerance zones. Maybe certain “zones” are implemented as geographic deployments of our services as backup; maybe it’d be too expensive from a latency perspective to have our traffic go to our backup instances during normal operation. Or maybe it costs too much money to always route traffic that way. So we may want to shape traffic round these considerations.

Maybe you want to route ingress client traffic like this, but what about inter-service communication? What about the routing for the same considerations between services that must converse with each other to satisfy client requests?

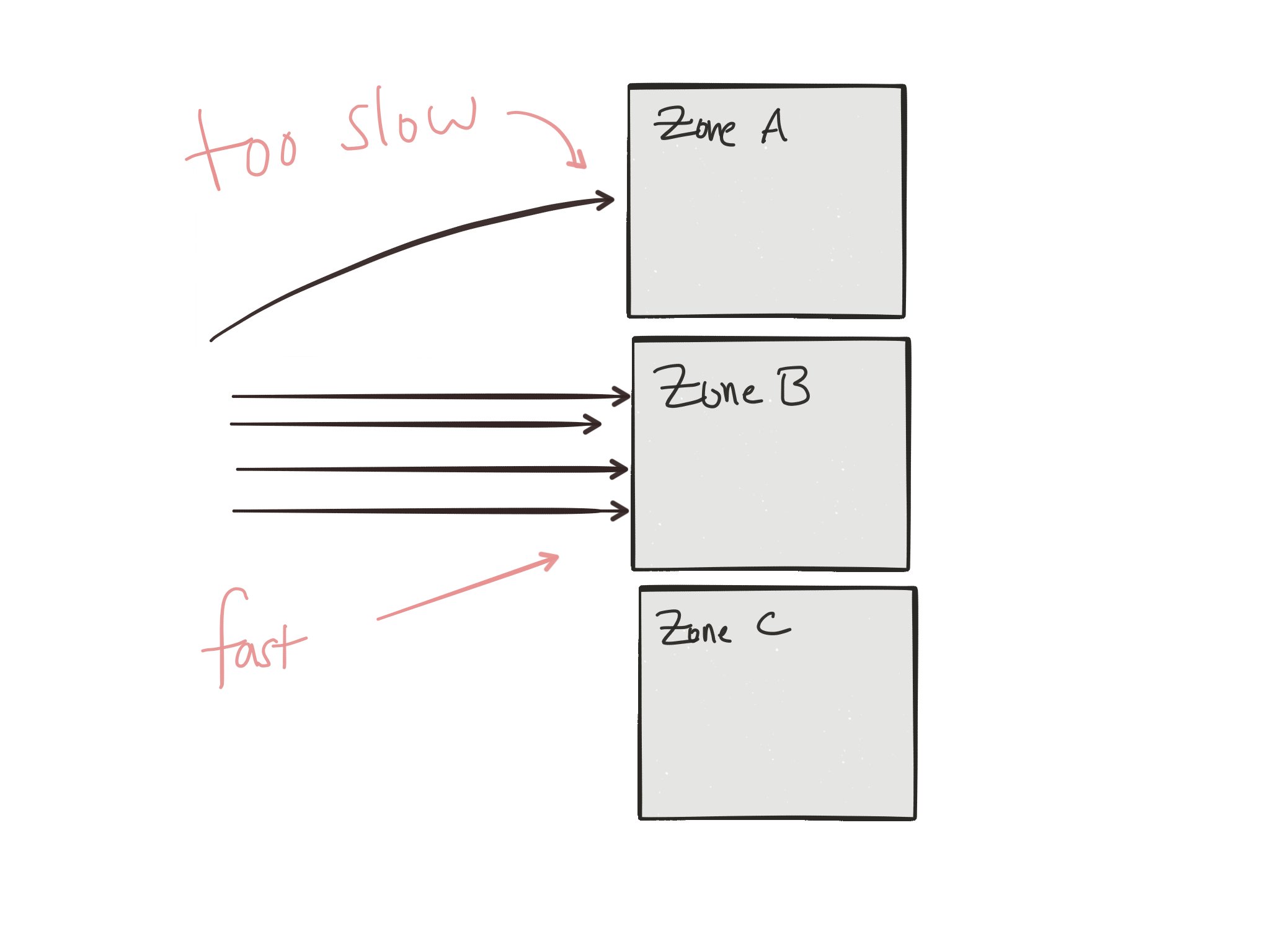

A variation of routing between fault tolerant zones could be routing and load balancing requests around outlier services or services that appear to periodically be slow? We’d like to adapt our routing to services that can keep up with our service calls. It makes very little sense to keep sending traffic to services that can’t seem to keep up.

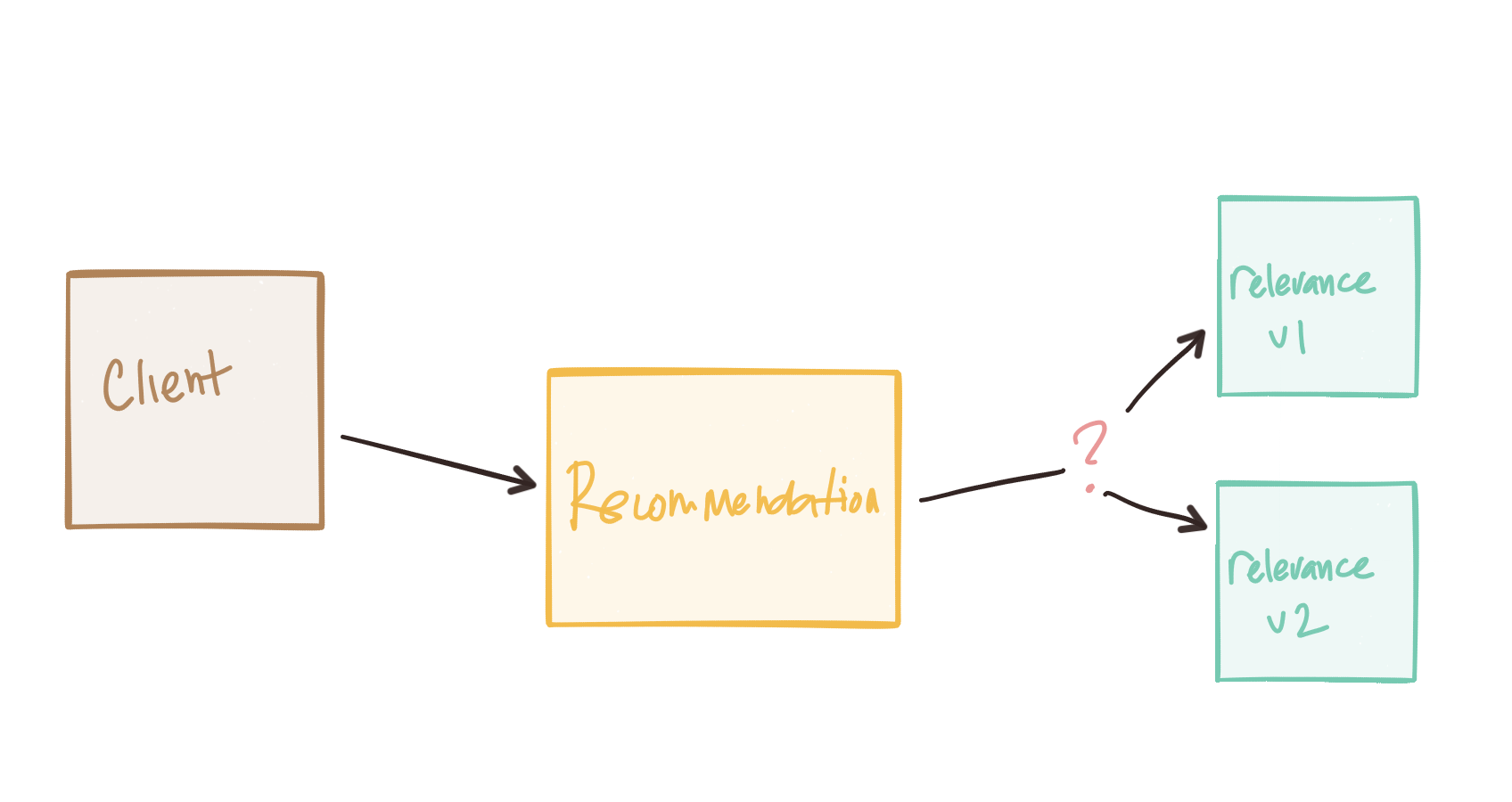

We can discuss even more trickiness with routing when we talk about how to deploy new versions of our services. As mentioned earlier, we’d like to maintain some level of autonomoy between services so we can quickly iterate and push out changes. We’d like to not break our dependent services, so what if we could route certain portions of traffic to our new versions and have this tied into our build and release strategies (ie, blue/green, A/B testing, canary releases). This gets complicated quickly. How do we determine what traffic to route? Maybe we’re doing testing in an ad-hoc “staging environment” that lives in production. Maybe we’re just doing an unannounced/dark launch. Maybe A/B tests. But what if we have some kind of state involved. We’d need to consider data schema evolution, multi-versioned database implementations, etc.

Service discovery

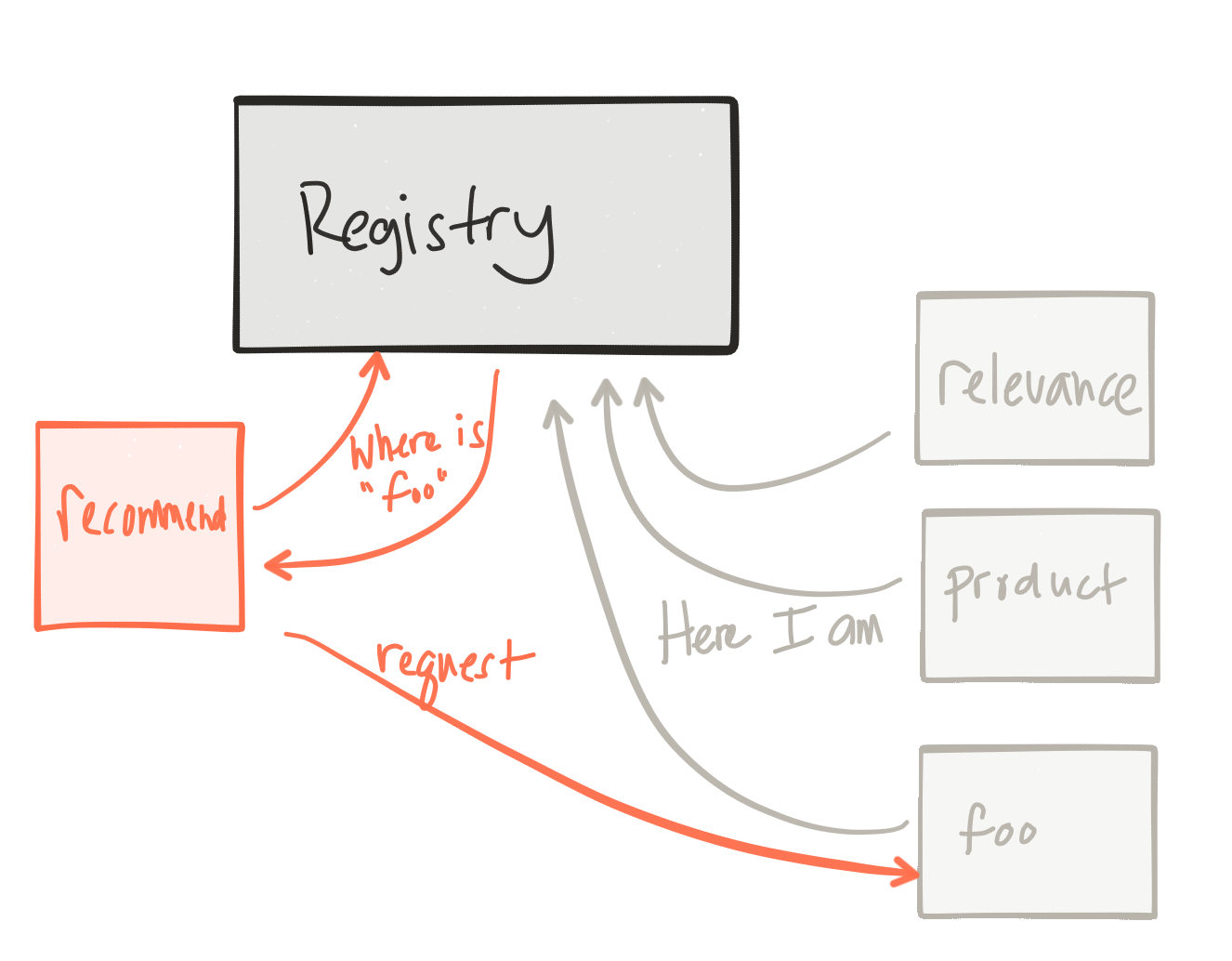

Alongside some of the resilience considerations discussed earlier, in an environment where expect failures, how do we discover our collaborator services? How do we know where they are and how to talk to them? In traditional, static topologies, our applications would be configured with the URLs/IPs of the services with which we’d need to talk. We’d also build these dependent services to “never fail”. But inevitably they’d fail (or partial fail) in some unforseen ways. But in an elastic environment this kind of behavior from our collaborators should be expected. These downstream services could autoscale, reshape to different fault-tolerant zones, or simply be killed and restarted by some automation. Clients of these services need to be able to discover them at run time and consume them regardless of what the topology looks like.

This is not a new problem to solve, but gets difficult in elastic environments. Things like DNS just don’t work (unless your’e lucky enough to run in Kubernetes :)) well.

Trusting your services architecture

I’ve saved the most important consideration/problem for last. Microservices is about making changes quickly to your system. If you cannot trust your system, you’re going to hesitate about making changes to it. You will slow down releases. If you deploy slower, this means you’ll have longer cycle times. Which means you’ll probably try to deploy bigger changes. You’ll need more coordination between teams. You’ll deveop a “this is how we’ve always done it attitude” until you’ve stifled your businesses IT capacity. Sound familiar?

You need to have trust in your systems architecture. With a monolith, you could at least trust if you’ve screwed something up it’s “somewhere in the monolith”. In a services architecture, all bets are off. How do you know what’s going on when things fail? You may have some complex combination of infrastructure (physical/virtual private/public/both .. containers?), with myriad deployments of middleware, services, frameworks, languages, and each service with its own release cadence. If a request is “slow” where do you even begin?

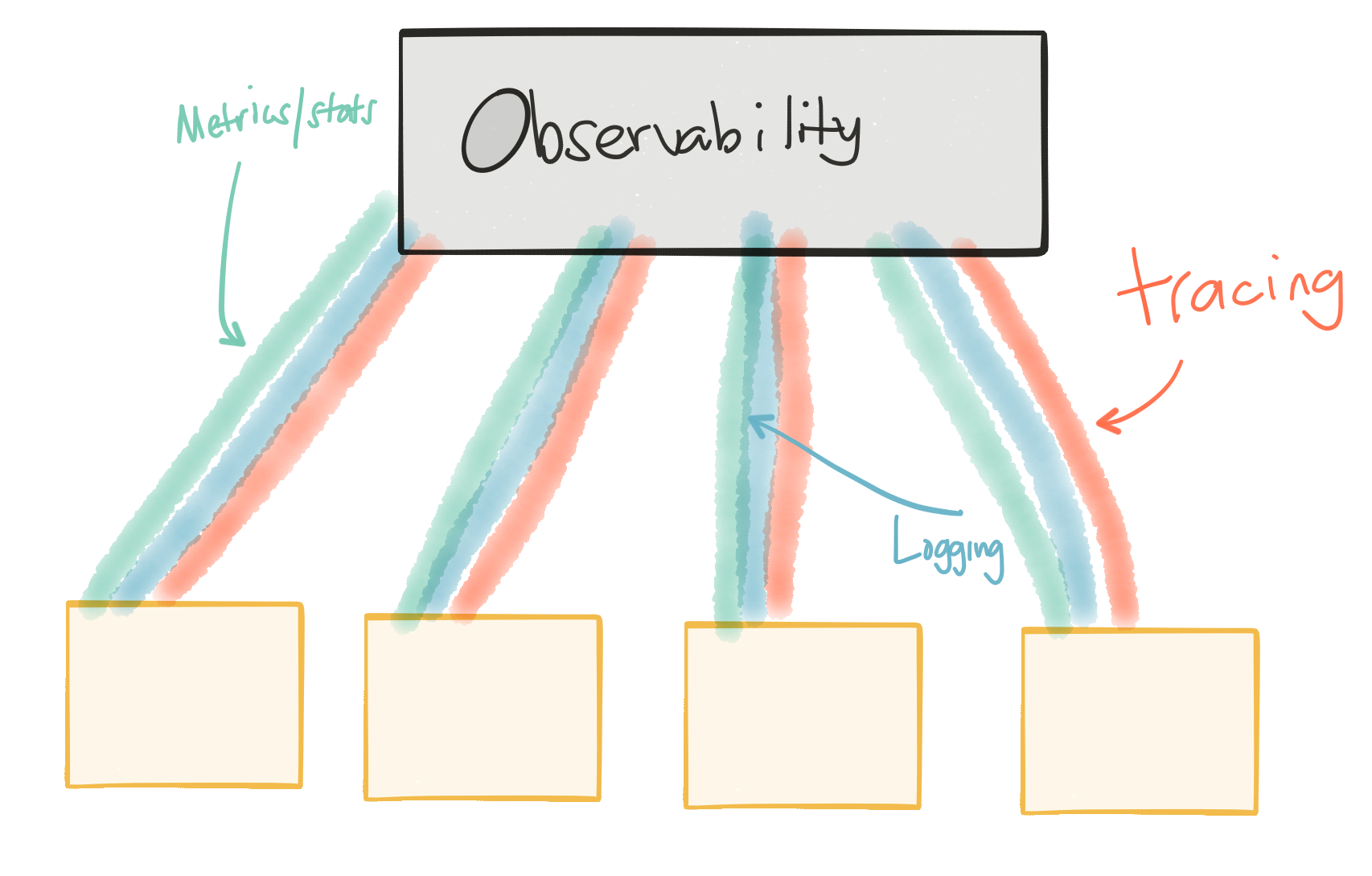

You need strong “observability” in your system. You need useful/effective logging, metrics, and tracing. If we’re quickly iterating and releasing services, we need to be data driven, understand the impact of our changes, rollback where it makes sense, or quickly release new versions to work around negative observations. All parts of our system need to be able to give reliable observability (logging/metrics/traces). The more we can trust this data, the more we can trust our services architecture and the more faith we’ll have for making changes.

So to recap: we’re solving for…

So to recap… and to drill a bit deeper, when our services call other services, we need to solve for:

- Service discovery

- Adaptive routing / client side load balancing

- Automatic retries

- Timeout controls

- back pressure

- Rate limiting

- Metrics/stats collection

- Tracing

- A/B testing / traffic shaping / request shadowing

- Service refactoring / request shadowing

- Service deadline/timeout enforcement across service calls

- Security between services

- Edge gateway/router

- Surgical / fine / per-request routing

- Forced service isolation / outlier detection

- Fault injection (ie, injecting delays? dropping ingress/egress packets?)

- Internal releases/dark launches

So how do you propose doing this? What did other people do?

If you look at how the Google/Twitter/Amazon/Netflix folks solved this, you could say they brute forced a solution for this. They (simplistic explanation) basically said “okay we’re going to use Java/C++/Python and invest untold amounts of brute engineering force to build libraries to help our developers solve for this.”. Google created Stubby. Twitter created Finagle, Netflix created and opensourced Netflix OSS, etc. Others have done this as well, although maybe not at the level and amount of investment that some of the internet companies did. Even we (fabric8 team) did this with the original Fabric8.io 1.x (deprecated).

For anyone else, there is a single big problem with this approach:

You’re not Netflix.

I don’t mean this in a condescending way. I just mean its not practical to invest substantial amounts of engineering/money to solve for these problems the way they did. The type of companies we see interested in microservices are interested in doing so for speed to value and innovation; this is an area they don’t have expertise in.

So maybe you could just re-use their solutions?

That leads to another quite interesting problem:

You’ll end up with a very complicated, ad-hoc, partially implemented solution

Think about it this way. A lot of customers I interact with are Java shops. They think about solving this problem for Java services. So naturally they gravitate to Netflix OSS or Spring Cloud or something. That’s awesome! But what about their NodeJS services? What about their Python services? What about their legacy applications? What about, dare I say, their perl scripts?

Each language has its own implementation of these problems. Each is implemented to different quality. It’s not as simple as grabbing open-source libraries and stuffing them in your application. You will have to test and validate each and every implementation. YOU are responsible for your services architecture, not these libraries. Chances are high this proliferation of implementations/languages/versions will quickly become an insurmountable complexity.

Another architecture smell I see:

We’re implementing lower-level networking functions at the application layer

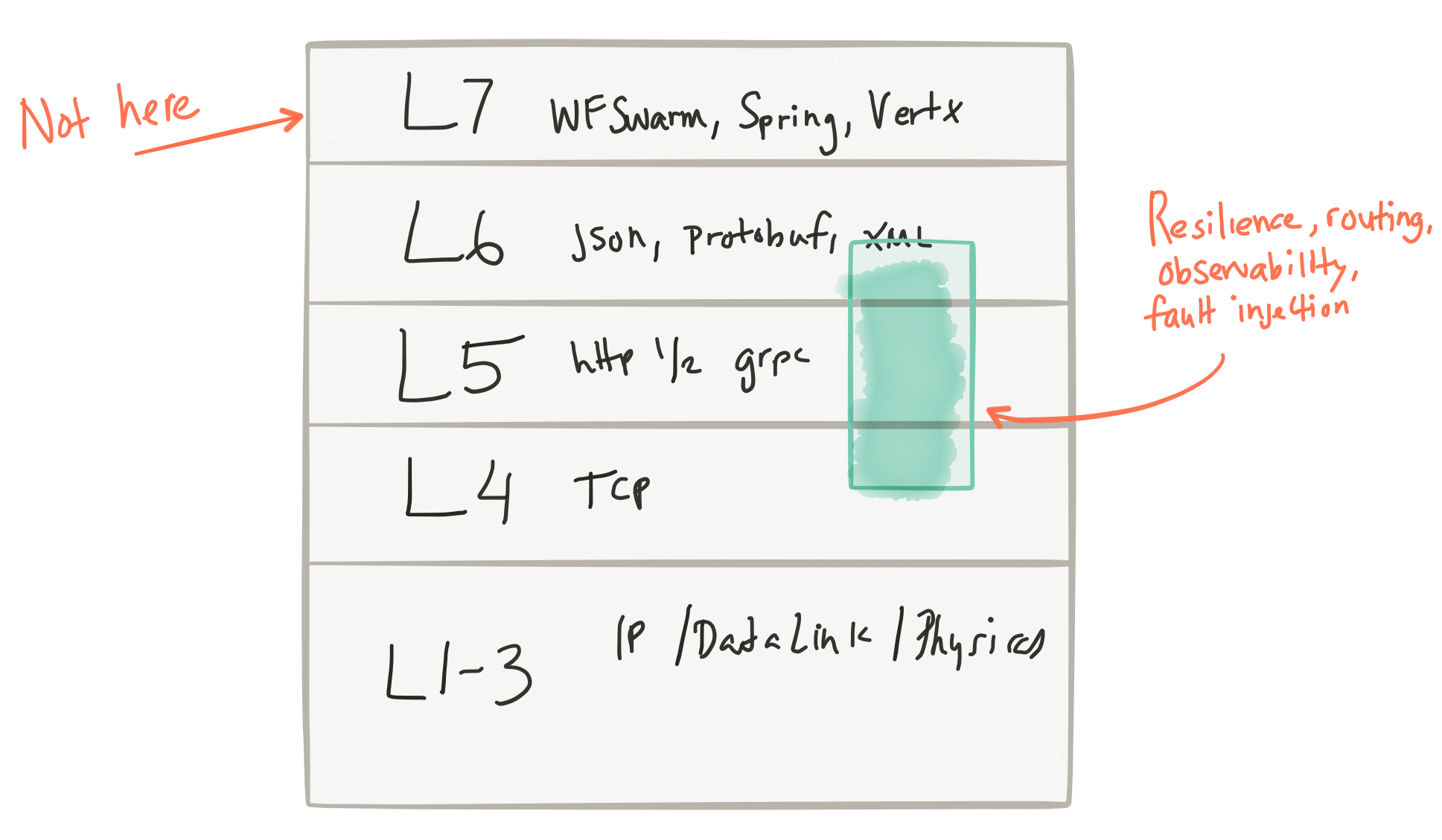

I love the talks that Oliver Gould from Buoyant gives when he mentions that these issues (routing, retries, rate limiting, circuit breaking, etc, etc) are really layer 5 considerations:

So why do we complicate our applications with these things? We’ve been trying to solve for these problems in the applications by creating libraries (a library that does circuit breaking, one that does service discovery, one that does tracing, a different one that does stats collections, even more for doing complex routing, etc) and jamming those into our application space (as dependencies, transitive dependencies, library calls, etc). What happens if your service developer forgets to add a part of this implementation (tracing for example)? So the onus is on each developer to implement these properly, bring in the right libraries, compose them in their code, etc.

Not to mention some of the frameworks that try to alleviate this with magic configurations of annotations in the Java space. The goal of trust, observability, debuggability, etc, is missed with an approach like this.

As I’ve mentioned in my “microservices 2.0 blog”, I am partial to an implementation that’s able to do this with a more elegant approach.

So where does that leave us?

IMHO this is where a service-proxy/sidecar pattern can help. If we can solve for these constraints:

- reduce any application-level awareness to trivial libraries if any

- implement all of these features in a single place, not strewn about a dumping ground of dependencies

- make observability a first-class design goal

- make it transparent to our services, including legacy services

- have very low overhead/resource implications

- work for any/all languages/frameworks

- push these considerations to lower levels of the stack (see above)

…then I’d think we’d be on to a more elegant solution to these problems. Ask yourself:

Do I spend the next few years implementing my services architecture using technology built for 5+ years ago?

Some interesting technology that’s been percolating from some recent companies at the vanguard of microservices to implement the service-proxy sidecar pattern include:

- Linkerd from https://buoyant.io

- Envoy from Lyft Engineering

- Traeffik from https://containo.us

In the next blog post, we’ll look at each of these implementations in detail and more specifically how to use them on Kubernetes.

I’ve run out of steam for this blog, and if you’ve followed me until this point, many thanks. Follow me @christianposta for the follow-on blog to this.