In the first part (part I) we introduced a strategy to bring microservices to our architecture without disrupting the current request flows and business value by looking at a concrete example. In the second part, we started looking at accompanying technology that aligns with our architectural strategy and goals. In this third part, we continue the solution from part II by focusing on what to do about adding a new service that may need to share data with the monolith (at least initially) and into some more complex deployment scenarios. We also explore consumer contract testing with Arquillian Algeron and how we can use that to get a handle on API changes in our services architecture.

Follow along (@christianposta) on twitter or http://blog.christianposta.com for the latest updates and discussion.

You can find Part I and Part II.

Technologies

The technologies we’ll use (in part II, III, and IV) to help guide us on this journey:

- Developer service frameworks (Spring Boot, WildFly, WildFly Swarm)

- API Design (APICur.io)

- Data frameworks (Spring Boot Teiid, Debezium.io)

- Integration tools (Apache Camel)

- Service mesh (Istio Service Mesh)

- Database migration tools (Liquibase)

- Dark launch / feature flag framework (FF4J)

- Deployment / CI-CD platform (Kubernetes / OpenShift)

- Kubernetes developer tools (Fabric8.io)

- Testing tools (Arquillian, Pact/Arquillian Algeron, Hoverfly, Spring-Boot Test, RestAssured, Arquillian Cube)

If you’d like to follow along, the sample project I’m using is based on the TicketMonster tutorial on http://developers.redhat.com but has been modified to show the evolution from monolith to microservice. You can find the code and documentation (docs still in progress!) here on github: https://github.com/ticket-monster-msa/monolith

We left off in part II by going down the path of adding a new microservice (Orders/Booking) that will be split out from our monolith. We began that step by exploring an appropriate API by simulating it with Hoverfly

Connect the API with an implementation

Revisit Considerations

- The extracted/new service has a data model that has tight coupling with the monolith’s data model by definition

- The monolith most likely does not provide an API at the right level to get this data

- Shaping the data even if we do get it requires lots of boiler plate code

- We can connect directly to the backend database temporarily for read-only queries

- The monolith rarely (if ever) changes its database

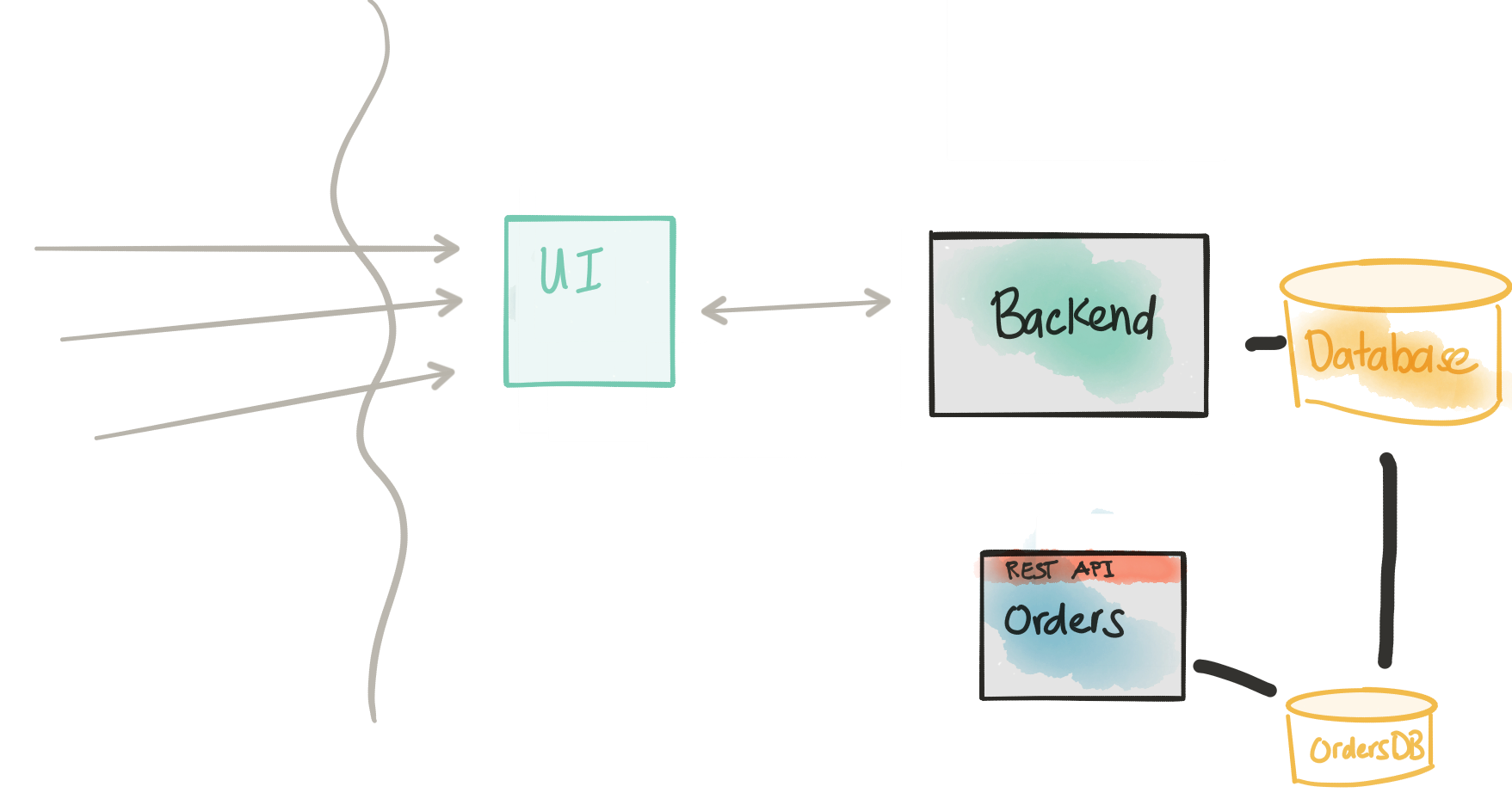

In part I we hinted at an solution involving connecting right up to the monolith’s database. In our example, we need to do this because the data in that database is going to initially start off being the life-blood of our new Orders service that we’re trying to decompose from the monolith. Additionally, we want to introduce this new service, allow it to take load, and have a consistent view with what’s in the monolith; ie, we’ll be running both concurrently for a period of time. Note, this maneuvering strikes right at the heart of our decomposition: we cannot just magically start calling a new microservice that properly encapsulates all of the logic of booking/ordering without impacting current load.

What alternatives do we have if we don’t want to connect right up to the monolith database? I can think of a few… feel free to comment or tweet at me if you want to voice other suggestions:

- Use the existing API exposed by the monolith

- Create a new API specifically for accessing the monolith’s database; call it anytime we need data

- Do an ETL from the monolith to our new service so we have the data already

Using existing API

If you can do this, definitely explore it. Often times, however, the existing APIs are quite coarse grained, not intended for lower-level use, and may need a lot of massaging to get into the desired data model you would like in your new service. For each incoming call your new service, Orders service in this example, you’d need to query (possibly multiple endpoints) the legacy/monolith API and engineer the response to your liking. There’s nothing inherently wrong with this unless you start taking short cuts that let your monolith/legacy API/data model strongly influence your new service’s data model. Even though, at least in my example, the data model may be similar at first, we want to quickly iterate (using DDD) and get the right domain model not just a normalized data model.

Create a new lower-level API

If the existing monolith API is too coarse grained (or doesn’t exist at all), or you don’t want to promote re-using it, you could instead create your own lower-level API that connects to the monolith’s database directly and expose the data at a level the new Orders service may need it. This may be an acceptable solution as well. On the other hand what I’ve experienced is that the new Orders service ends up writing lots of queries/API calls to this new lower-level interface and doing in-memory joins on the responses (similar to the previous option). It could also feel like we’re implementing a database. Again, nothing inherently wrong with this, but this leaves a lot of boiler plate code for the Orders service to write – a lot of it used as a temporary, interim, solution.

Do an ETL from monolith to our new service

At some point, we may indeed need to do this. However, at the point when we’re working on the domain model of the new service, we may not want to deal with the old monolith structure. Also, we intend to run the new services alongside the monolith at the same time; we expect both to possibly take traffic. If we do the ETL approach, we’ll need a way to keep the Orders service up-to-date as things can get out of sync quickly. This ends up being a bit of a nightmare.

As a developer of the new Orders service, we want to think in terms of the domain model (note: i didn’t say data model – there’s a difference) that makes sense for our service. We want to eliminate, as much as possible, the influence of outside implementations that could serve to compromise our domain model. The distinction: a data model shows how pieces of the (static) data in our system relate to each other, possibly giving guidance for how things get stored in a persistence layer. Domain models are used for describing the behavior of the solution space of our domain and tend to focus more on usecase/transaction behaviors; ie, the concepts or models we use to communicate what the problem is. DDD guru Vaughn Vernon has a great series of essays that go into this distinction in more detail.

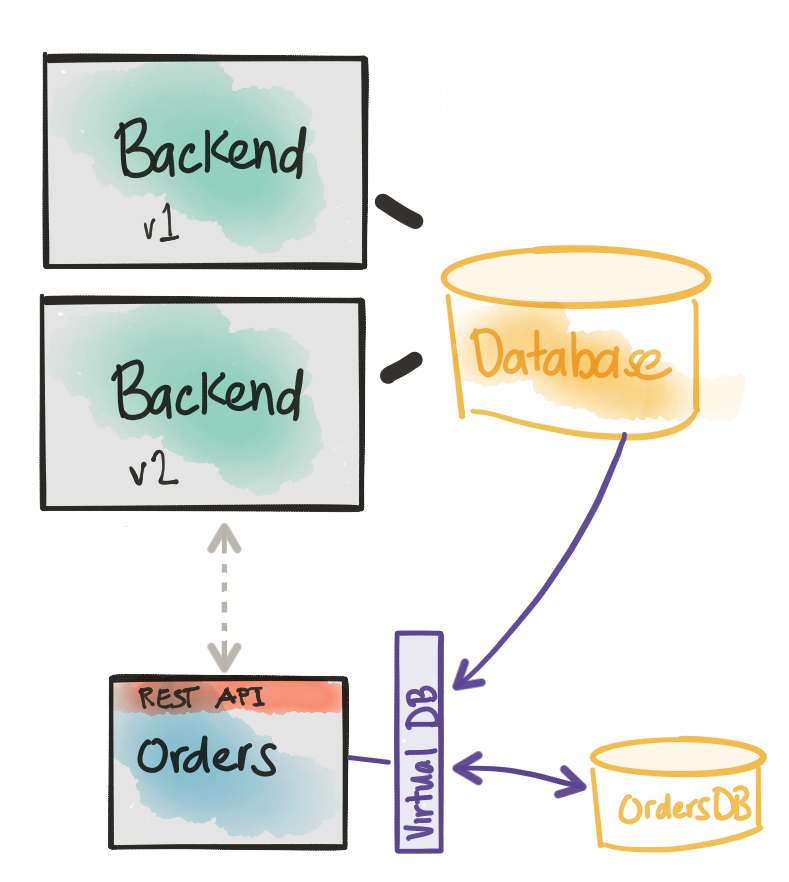

The solution that I’ve used in the Orders service for Ticket Monster orders service is to use an opensource project named Teiid that helps reduce/eliminate the boiler plate of munging data models into our ideal domain model. Teiid has traditionally been a data federation software with the ability to take disparate datasources (Relational DBs, NoSQL, Flat files, etc) and present them as a single virtualized view. Typically this would be used by data analytics folks to aggregate data for reporting purposes, etc. but we’re more interested in how developers can use it solve the above problem. Luckily folks from the Teiid community, especially Ramesh Reddy, created some nice extensions to Teiid and Spring Boot to help eliminate the boiler plate that comes along with solving this problem.

Introducing Teiid Spring Boot

Again, to re-state the problem: we must focus on our service’s domain model, but initially the data that backs the domain model will still be in our monolith/backend database. Can we virtually merge the structure of the monolith’s data model with our desired domain model and eliminate boiler plate code dealing with combining this data?

Teiid Spring Boot allows us to focus on our Domain model, annotate them with JPA @Entity annotations as we would with any model, and map them to our own new database as well as virtually map the monolith’s database. To get started with teiid-spring-boot all you need is to import the following dependency:

<dependency>

<groupId>org.teiid.spring</groupId>

<artifactId>teiid-spring-boot-starter</artifactId>

<version>1.0.0-SNAPSHOT</version>

</dependency>This is a starter project that will hook into Spring’s auto configure magic and attempt to set up our virtual database (backed by the monolith’s database and our real, physical database owned by this service).

Now we need to define the data sources in Spring Boot for each of the backends. In this example case I’ve used two MySQL databases, but that’s just a detail. We’re not limited to both data sources being the same, nor are we limited to RDBMs. Here’s an example:

spring.datasource.legacyDS.url=jdbc:mysql://localhost:3306/ticketmonster?useSSL=false

spring.datasource.legacyDS.username=ticket

spring.datasource.legacyDS.password=monster

spring.datasource.legacyDS.driverClassName=com.mysql.jdbc.Driver

spring.datasource.ordersDS.url=jdbc:mysql://localhost:3306/orders?useSSL=false

spring.datasource.ordersDS.username=ticket

spring.datasource.ordersDS.password=monster

spring.datasource.ordersDS.driverClassName=com.mysql.jdbc.DriverLet’s also configure teiid-spring-boot to scan our domain models for their virtual mappings to the monolith. In application.properties let’s add this:

spring.teiid.model.package=org.ticketmonster.orders.domainTeiid Spring Boot allows us to specify our mappings as annotations on our @Entity definitions. Here’s an example (see the full implementation and full set of domain objects on github):

@SelectQuery("SELECT s.id, s.description, s.name, s.numberOfRows

AS number_of_rows, s.rowCapacity AS row_capacity, venue_id, v.name

AS venue_name FROM legacyDS.Section s

JOIN legacyDS.Venue v ON s.venue_id=v.id;")

@Entity

@Table(name = "section", uniqueConstraints=@UniqueConstraint(columnNames={"name", "venue_id"}))

public class Section implements Serializable {

@Id

@GeneratedValue(strategy = IDENTITY)

private Long id;

@NotEmpty

private String name;

@NotEmpty

private String description;

@NotNull

@Embedded

private VenueId venueId;

@Column(name = "number_of_rows")

private int numberOfRows;

@Column(name = "row_capacity")

private int rowCapacity; In the above example, we used the @SelectQuery to define the mapping between the legacy data source (legacyDS.*) and our own domain model. Note, often times these mappings can have lots of JOINs etc to get the data in the right shape for our model; it’s better to write this JOIN once in an annotation that try write lots of boiler plate code to deal with this across a REST API(not just the querying, but the actual mapping to our intended domain model). In the above case, we just mapped from the monolith’s databae to our domain model – but what if we need to merge in our own database? Something like this can be done (see the full impl in the Ticket.java entity):

@SelectQuery("SELECT id, CAST(price AS double), number, rowNumber

AS row_number, section_id, ticketCategory_id

AS ticket_category_id, tickets_id AS booking_id

FROM legacyDS.Ticket " +

"UNION ALL SELECT id, price, number, row_number, section_id, ticket_category_id,

booking_id FROM ordersDS.ticket")Note in this sample, we’re unioning both of the views (from the monolith database and our own local Orders database) with the keyword UNION ALL.

What about Updates or Inserts?

For example, our Orders service is supposed to store Orders/bookings. We can add an @InsertQuery annotation on the Booking DDD entity/aggregate like this:

@InsertQuery("FOR EACH ROW \n"+

"BEGIN ATOMIC \n" +

"INSERT INTO ordersDS.booking (id, performance_id, performance_name, cancellation_code, created_on, contact_email ) values (NEW.id, NEW.performance_id, NEW.performance_name, NEW.cancellation_code, NEW.created_on, NEW.contact_email);\n" +

"END")See the documentation for the rest of the teiid-spring-boot annotations that we can use.

You can see here when we persist a new Booking (JPA, Spring Data, whatever) the virtual database knows to store it into our own Orders database. If you prefer to use Spring Data, you can still take advantage of teiid-spring-boot. Here’s an example from the teiid-spring-boot samples:

public interface CustomerRepository extends CrudRepository<Customer, Long> {

@Query("select c from Customer c where c.ssn = :ssn")

Stream<Customer> findBySSNReturnStream(@Param("ssn") String ssn);

}If we have the proper teiid-spring-boot mapping annotations, this spring-data repository will understand our virtual database layer correctly and just let us deal with our domain model as we would expect.

To re-iterate; this is a point-in-time solution for the initial steps for microservice decomposition; it’s not intended to the the final solution. We’re still iterating on that in our running example here. We’re intending to reduce the boiler plate and nastiness that can arise with doing the mapping/translation, etc by hand.

If you’re still bent on standing up a simple API for lower-level data access to the monolith database (again, as a temporary solution), then teiid-spring-boot is still your friend. You can very quickly expose this kind of API with no code using the odata integration we have with teiid-spring-boot. Please checkout the odata module for more (note, we’re still working on more docs for the project!)

At this point in the decomposition, we should have an implementation of our Orders service with a proper API, domain model, connecting to our own database, and temporarily creating a virtual mapping to our monolith database that we can use inside our domain model. Next we need to deploy it into production and dark launch it.

Start sending shadow traffic to the new service (dark launch)

Revisit Considerations

- Introducing the new Orders service into the code path introduces risk

- We need to send traffic to the new service in a controlled manner

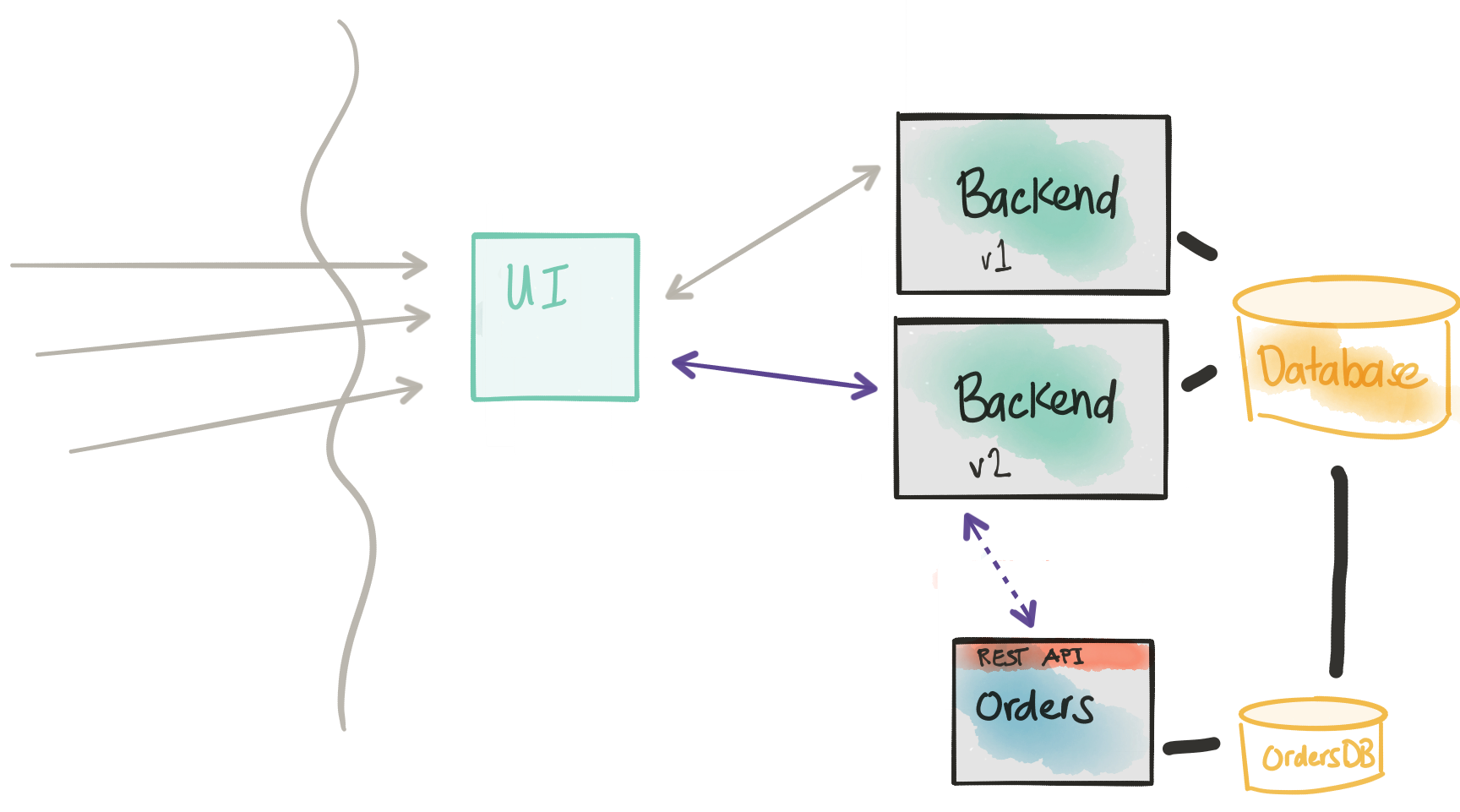

- We want to be able to direct traffic to the new service as well as the old code path

- We need to instrument and monitor the impact of the new service

- We need ways to flag transactions as “synthetic” so we don’t end up in nasty business-consistency problems

- We wish to deploy this new functionality to certain cohorts/groups/users

Following along from part I for this section, we are going to modify the monolith to make a call to our new Orders service. As described in part I, we’ll use some techniques from Michael Feather’s book to wrap/extend the existing logic in our monolith to call our new service. For example, our monolith looked like this for the createBookings implementation:

@POST

@Consumes(MediaType.APPLICATION_JSON)

public Response createBooking(BookingRequest bookingRequest) {

try {

// identify the ticket price categories in this request

Set<Long> priceCategoryIds = bookingRequest.getUniquePriceCategoryIds();

// load the entities that make up this booking's relationships

Performance performance = getEntityManager().find(Performance.class, bookingRequest.getPerformance());

// As we can have a mix of ticket types in a booking, we need to load all of them that are relevant,

// id

Map<Long, TicketPrice> ticketPricesById = loadTicketPrices(priceCategoryIds);

// Now, start to create the booking from the posted data

// Set the simple stuff first!

Booking booking = new Booking();

booking.setContactEmail(bookingRequest.getEmail());

booking.setPerformance(performance);

booking.setCancellationCode("abc");

// Now, we iterate over each ticket that was requested, and organize them by section and category

// we want to allocate ticket requests that belong to the same section contiguously

Map<Section, Map<TicketCategory, TicketRequest>> ticketRequestsPerSection

= new TreeMap<Section, java.util.Map<TicketCategory, TicketRequest>>(SectionComparator.instance());

for (TicketRequest ticketRequest : bookingRequest.getTicketRequests()) {

final TicketPrice ticketPrice = ticketPricesById.get(ticketRequest.getTicketPrice());

if (!ticketRequestsPerSection.containsKey(ticketPrice.getSection())) {

ticketRequestsPerSection

.put(ticketPrice.getSection(), new HashMap<TicketCategory, TicketRequest>());

}

ticketRequestsPerSection.get(ticketPrice.getSection()).put(

ticketPricesById.get(ticketRequest.getTicketPrice()).getTicketCategory(), ticketRequest);

}Actually, there’s a lot more to this code – just like any good monolith, there are very long, complicated methods that can be difficult to understand what’s going on. We’re going to change it to something like this:

@POST

@Consumes(MediaType.APPLICATION_JSON)

public Response createBooking(BookingRequest bookingRequest) {

Response response = null;

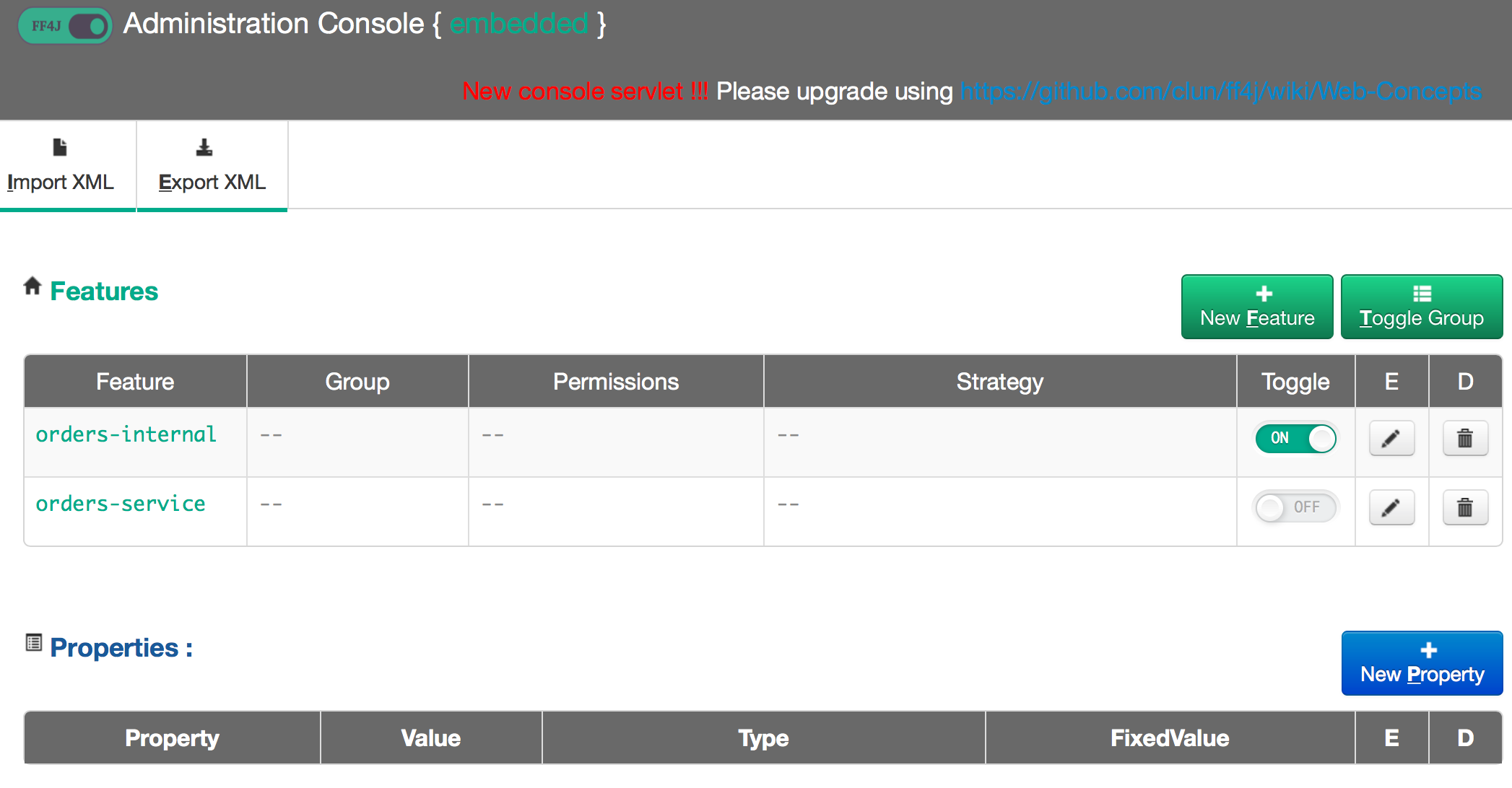

if (ff.check("orders-internal")) {

response = createBookingInternal(bookingRequest);

}

if (ff.check("orders-service")) {

if (ff.check("orders-internal")) {

createSyntheticBookingOrdersService(bookingRequest);

}

else {

response = createBookingOrdersService(bookingRequest);

}

}

return response;

}This method is much smaller, more organized, and easier to follow. But what’s going on here? What’s this ff.check(...) stuff?

A key point to make here is that we’re altering the monolith as little as we can; ideally we have unit/component/integration/system tests to help validate our changes don’t break anything. If not, refactor tactically to be able to get tests in place.

As part of the changes we make, we don’t want to alter the existing call flow: we move the old implementation to a method called createBookingInternal and leave it as is. But we also add a new method that will be responsible for the new code path that calls the Orders service. We are going to use a feature-flag library that will allow us to do a couple things:

- Full runtime/configuration control over which implementation to use for orders

- Disable the new functionality

- Enable BOTH the new functionality AND the old functionality simultaneously

- Completely switch over to the new functionality

- Kill switch all functionality

We’re using Feature Flags 4 Java (FF4j), but there are alternatives for other languages including a hosted SaaS providers like Launch Darkly. Of course you could write your own framework to do this, but these existing projects offer out of the box capabilities. This is a very similar approach to Facebook’s (and others) framework for controlling releases. Refer back to the discussion about the difference between a deployment and a release.

To use FF4j, let’s add the dependency to our pom.xml

<dependency>

<groupId>org.ff4j</groupId>

<artifactId>ff4j-core</artifactId>

<version>${ffj4.version}</version>

</dependency>Then we can declare features in our ff4j.xml file (and group them, etc. please see the ff4j documentation for more details on the more complicated feature/grouping features:

<features>

<feature uid="orders-internal" enable="true" description="Continue with legacy orders implementation" />

<feature uid="orders-service" enable="false" description="Call new orders microservice" />

</features>Then we can instantiate an FF4j object and use it to test whether features are enabled in our code:

FF4j ff4j = new FF4j("ff4j.xml");

if (ff4j.check("special-feature")){

doSpecialFeature();

} The out of the box implementation uses the ff4j.xml configuration file to specify features. The features can then be toggled at runtime, etc (see below), but before we keep going I want to point out that the features and their respective status (enable/disable) should be backed by a persistent store in any kind of non-trivial deployment. Please take a look at the FeatureStore docs on the ff4j site.

We also want a way to configure/influence the status of the features during runtime. FF4j has a web console that you can deploy to view/influence the status of the features in an application:

By default, we’ll deploy with only the legacy feature enabled. That is, by default we should see no change in the code execution paths and service behavior. We can then canary this deployment and use the feature flags to enable BOTH the legacy code path as well as the new path that calls our new Orders service. For some services, we may not need to pay any more attention that just enabling the second code path. But for something that changes state, we’ll need a way to signal this is a “test” or “synthetic” transaction. In our case, when we have BOTH the legacy and new code path enabled at the same time, we’ll mark the messages sent to the Orders service as “synthetic”. This gives a hint to the Orders service that we should just process it as a normal request, but then discard or rollback the result. This is hugely valuable to get a sense of what the new code path is doing and give us a chance to compare to the old path (ie, compare results, side effects, time/latency impact, etc). If we JUST enable the new code path and disable the old code path, we’ll send live requests (without the synthetic indicator/flag).

Specifying service contracts

At this point, we should probably write the code to connect the monolith to the new Orders service for booking and orders flows. Now’s a good time for the monolith to express any requirements in terms of contract or data that it may care about when it calls the Orders service. Of course, the Orders service is an independent, autonomous service and promises to provide a certain set of functionalities/SLAs/SLOs, etc, but when we start building distributed systems it’s important to understand assumptions about service interaction and make them explicit.

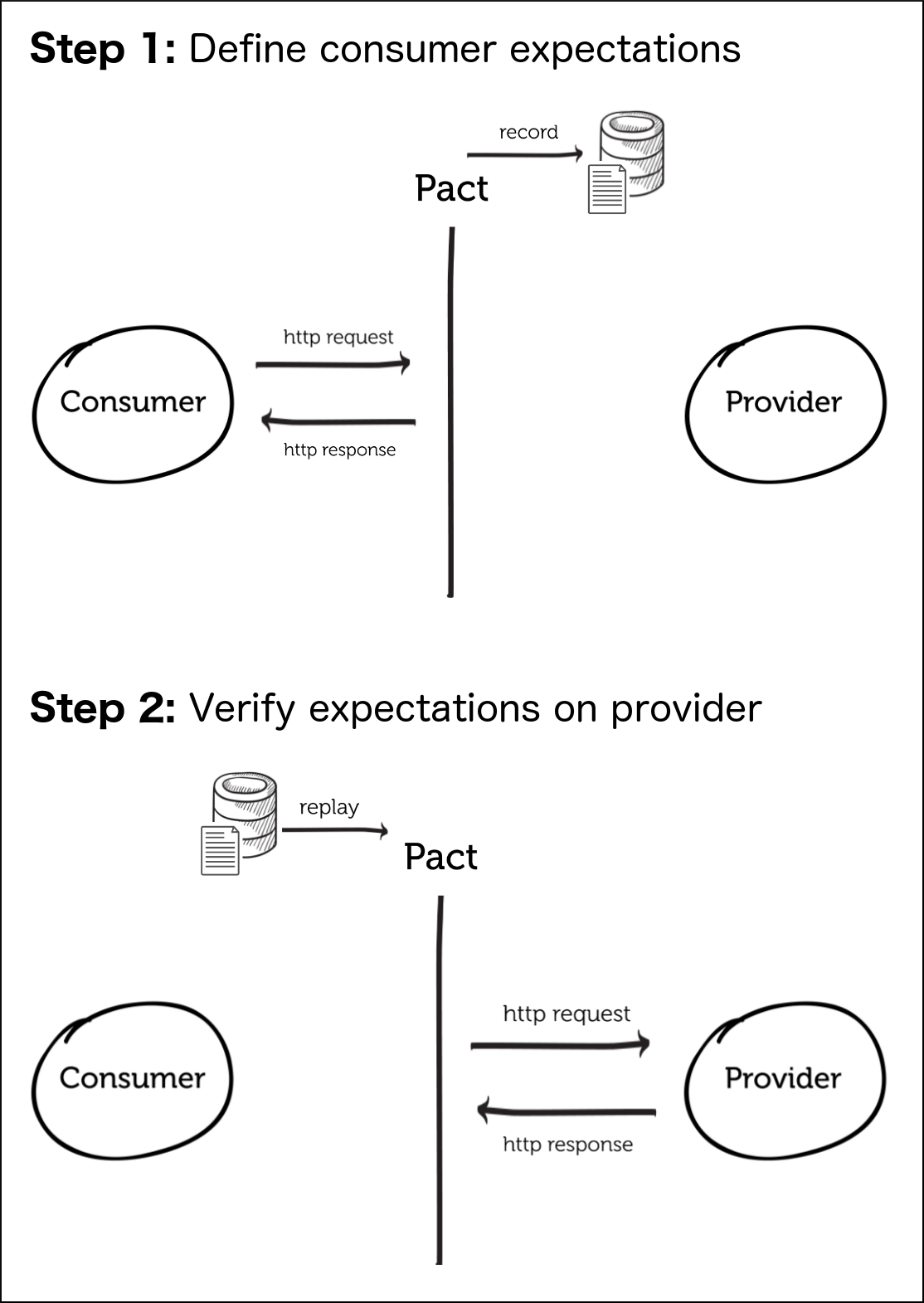

Typically we consider contracts from the point of view of the provider. In this case, we’re looking at the problem from the consumer’s point of view. What do the consumers actually use or value from a service provider? Can we provide this feedback to the provider so they can understand what’s actually being used of their service and about what to take care when making changes to its service; ie, we don’t want to break existing compatibility. We’re going to leverage the idea of consumer driven contracts to help make assumptions explicit. We’re going to use a project named Pact which is a language agnostic documentation format for specifying contracts between services (with an emphasis on consumer-driven contracts). I believe Pact was started a while back by the folks over at DiUS, a technology company in Australia.

The image above comes from the Pact documentation

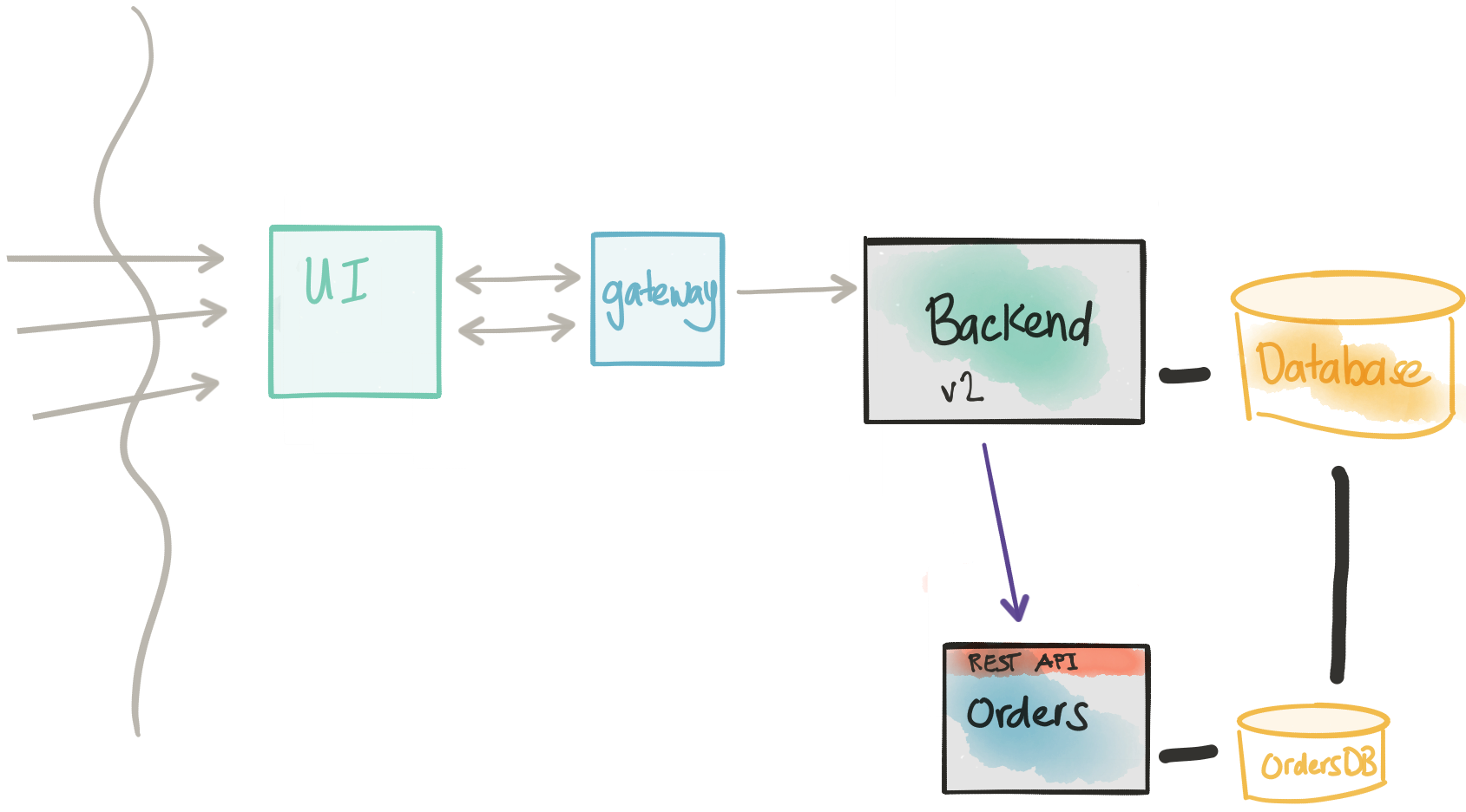

Let’s look at an example from our backend service. We’re going to create a consumer contract rule for our backend-v2 application that outlines the expectations from the service provider (the Orders service). When we issue a POST HTTP request to /rest/bookings then we can assert some expectations.

@Pact(provider="orders_service", consumer="test_synthetic_order")

public RequestResponsePact createFragment(PactDslWithProvider builder) {

RequestResponsePact pact = builder

.given("available shows")

.uponReceiving("booking request")

.path("/rest/bookings")

.matchHeader("Content-Type", "application/json")

.method("POST")

.body(bookingRequestBody())

.willRespondWith()

.body(syntheticBookingResponseBody())

.status(200)

.toPact();

return pact;

}When we call the provider service and pass in a particular body, we expect an HTTP 200 and a response that matches our contract. Let’s take a look. First, here’s how we specify the booking request body:

private DslPart bookingRequestBody(){

PactDslJsonBody body = new PactDslJsonBody();

body

.integerType("performance", 1)

.booleanType("synthetic", true)

.stringType("email", "foo@bar.com")

.minArrayLike("ticketRequests", 1)

.integerType("ticketPrice", 1)

.integerType("quantity")

.closeObject()

.closeArray();

return body;

}Pact-jvm allows us to hook into our favorite testing framework (JUnit in this case) with the pact-jvm-junit modules. If we’re using Arquillian, which you should be, for component and integration tests, we can hook Pact into our Arquillian tests with Arquillian Algeron. Alegeron extends Pact by making it easy to use from Arquillian tests and also adds functionality that you’d have to otherwise build out yourself (and is crucial for CI/CD pipelines): ability to automatically publish contracts to a contract broker and pull down contracts from a broker when testing. I highly recommend you take a look at Arquillian and Arquillian Algeron for doing consumer-contract testing for your Java applications.

We can create the PactDslJsonBody fragments and just use “wildcard” or “pass anything in this field” semantics. For example, body.integerType("attr_name", default_value) lets us specify that “there will be an attribute named X with a default value”.. if we leave the default value parameter out, then the value can really be anything. In this snippet we’re just specifying the structure of the request. Note, we specify an attribute named synthetic and for requests where this property is true, we’ll expect a response that has a certain structure.

And here’s where we declare our consumer contract (the response):

private DslPart syntheticBookingResponseBody() {

PactDslJsonBody body = new PactDslJsonBody();

body

.booleanType("synthetic", true);

return body;

}This is pretty simple example: for this test, we expect that the response will have an attribute synthetic: true. This is important because when we send synthetic bookings, we want to make sure the Orders service acknowledges this indeed was treated as a synthetic request. If we run this test, and it completes successfully, we end up with this Pact contract in our target build directory (ie, in my case it goes into ./target/pacts

{

"provider": {

"name": "orders_service"

},

"consumer": {

"name": "test_synthetic_order"

},

"interactions": [

{

"description": "booking request",

"request": {

"method": "POST",

"path": "/rest/bookings",

"headers": {

"Content-Type": "application/json"

},

"body": {

"synthetic": true,

"performance": 1,

"ticketRequests": [

{

"quantity": 100,

"ticketPrice": 1

}

],

"email": "foo@bar.com"

},

"matchingRules": {

"header": {

"Content-Type": {

"matchers": [

{

"match": "regex",

"regex": "application/json"

}

],

"combine": "AND"

}

},

"body": {

"$.performance": {

"matchers": [

{

"match": "integer"

}

],

"combine": "AND"

},

"$.synthetic": {

"matchers": [

{

"match": "type"

}

],

"combine": "AND"

},

"$.email": {

"matchers": [

{

"match": "type"

}

],

"combine": "AND"

},

"$.ticketRequests": {

"matchers": [

{

"match": "type",

"min": 1

}

],

"combine": "AND"

},

"$.ticketRequests[*].ticketPrice": {

"matchers": [

{

"match": "integer"

}

],

"combine": "AND"

},

"$.ticketRequests[*].quantity": {

"matchers": [

{

"match": "integer"

}

],

"combine": "AND"

}

},

"path": {

}

},

"generators": {

"body": {

"$.ticketRequests[*].quantity": {

"type": "RandomInt",

"min": 0,

"max": 2147483647

}

}

}

},

"response": {

"status": 200,

"headers": {

"Content-Type": "application/json; charset=UTF-8"

},

"body": {

"synthetic": true

},

"matchingRules": {

"body": {

"$.synthetic": {

"matchers": [

{

"match": "type"

}

],

"combine": "AND"

}

}

}

},

"providerStates": [

{

"name": "available shows"

}

]

}

],

"metadata": {

"pact-specification": {

"version": "3.0.0"

},

"pact-jvm": {

"version": ""

}

}

}From here we can put our contract into Git, a Contract Broker, or onto a shared file system. On the provider side (Orders service) we can create a component test that verifies that the provider service does in fact fulfill the expectations in the consumer contract. Note, you could have many consumer contracts and we could test against all of them (especially if we make changes to the provider service – we can do an impact test to see what downstream users of our service may be impacted).

@RunWith(PactRunner.class)

@Provider("orders_service")

@PactFolder("pact/")

public class ConsumerContractTest {

private static ConfigurableApplicationContext applicationContext;

@TestTarget

public final Target target = new HttpTarget(8080);

@BeforeClass

public static void startSpring() {

applicationContext = SpringApplication.run(Application.class);

}

@State("available shows")

public void testDefaultState() {

System.out.println("hi");

}

}Note in this simple example, we’re pulling the contracts from a folder on the file system under ./pacts

Once we have our consumer-driven contract testing into place we can more comfortably make changes to our service. See the examples for the backend-v2 service as well as the provider Orders service for working examples of this.

Canary/Rolling Release to new service

Revisit Considerations

- We can identify cohort groups and send live transaction traffic to our new microservice

- We still need the direct database connection to the monolith because there will be a period of time where transactions will still be going to both code paths

- Once we’ve moved all traffic over to our microservice, we should be in position to retire the old functionality

- Note that once we’re sending live traffic over to the new service, we have to consider the fact a rollback to the old code path will involve some difficulty and coordination

Another important part of this scenario is that we need a way to just send a fraction of traffic through this new deployment that has the feature flags. We can use Istio to finely control exactly which backend gets called. For example, we’ve had backend-v1 deployed which is fully released and is taking the production load. When we deploy backend-v2 which has the feature flags controlling our new code path, we can canary that release with Istio similarly to how we did in the previous post. We can just send 1% of the traffic and slowly increase (5%, 25% etc) and observe the effect. We can also toggle the features so both legacy code paths and new code paths are enabled. This is a very poweful technique that allows us to significantly drive down the risk of our changes and our migration to a microservice architecture. Here’s an example Istio route-rule that does that for us:

apiVersion: config.istio.io/v1alpha2

kind: RouteRule

metadata:

name: backend-v2

spec:

destination:

name: backend

precedence: 20

route:

- labels:

version: v1

weight: 99

- labels:

version: v2

weight: 1Some things to note: at this point, we may have both legacy and new-code paths enabled with the new Orders service taking synthetic transactions. The canary described so far would be applied to 1% of traffic regardless of who they are. It may be useful to just release to internal users or a small segment of outside users first and actually send them through the live Orders service (ie, non-synthetic traffic). With a combination of surgical routing based on user and FF4j configuration grouping users into cohorts, we can enable the full code path to the new Orders service (live traffic, non-synthetic transactional workload). The key to this, however, is once a user has been directed to the live code path for Orders they should always be sent that way for future calls. This is because once an order is placed with the new service, it will not be seen in the monolith’s database. All queries/updates to that order for that user should always go through the new service now.

At this point we can observe the traffic patterns/service behavior and make determinations to increase the release aperture. Eventually we get to 100% traffic going to the new service.

What to do about the data not being in the monolith? You may opt to do nothing – the new Orders service is now the rightful owner of the Orders/Booking logic+data. If you feel you need some integration between the monolith for those new Orders, you could opt to publish events from your new Orders service with the order details. The monolith could then capture those events and store them in the monolith database. Other services could also listent for these events and react to them. The event publishing mechanism would be useful.

Again, this blog post has gotten too long! There are two sections left “Offline data ETL/migration” and “Disconnect/decouple the data stores”. I want to give those sections proper treatment so I’ll have to end here and make that Part IV! Part V will be the webcast/video/demo showing all of this working.